As a distributed systems company, we’ve had the privilege of speaking with dozens of vendors building crypto-adjacent solutions over the past few years. We’ve learned a lot along the way, especially about some of the key misconceptions that continue to challenge builders, users, investors, and other crypto stakeholders.

We’ve struggled with these misconceptions ourselves, in both the words and the code we write. In this post, we’ll present common misunderstandings about crypto that we’ve encountered in the hopes of providing clearer direction to others forging ahead in this space.

#1: Blockchains Are Intentionally Slow

First and foremost, blockchain is not intended to be a high performance or low latency solution. In fact, it may well be one of the least performant types of distributed system technology — and that’s no accident.

A blockchain is a persistent, transparent, and public append-only distributed ledger. It consists of a network of computers or nodes that collectively contain a shared history of transactions. Transaction data can be added to a blockchain and previous data cannot be changed (i.e. it is “immutable”). The nodes do not know or trust each other, meaning blockchain is a trustless mechanism of trade. This is convenient, as it does not require a middleman to facilitate exchanges. Instead, nodes must rely on using an agreed-upon method for validating new additions to the chain (e.g. Proof of Work or Proof of Stake).

As a result, blockchains must prevent Byzantine behavior whereby some nodes (either due to unreliability or to being a bad actor) present a risk to the system. Unfortunately, Byzantine fault-tolerance is notoriously slow1.

When organizations seek ways to speed up blockchain transactions, they introduce technical risk that could result in system failure or exploitation by a bad actor. Let’s look more into technical risk and a recent example.

#2: Technical Risk Is Significantly Underestimated

People who get involved with cryptocurrency are usually prepared for volatility — it’s all part of the gamble of adopting a fairly young asset type. As such, investors and vendors alike tend to keep an eye trained on volatility indices. However, as far as we can tell, these indices do not take into account technical risks when evaluating crypto. We believe many projects are much riskier than their current valuation.

Many builders attempt to optimize, scale, or reduce friction in blockchain systems. Sometimes these efforts are critically important — as we mentioned above, blockchains are typically very slow, sometimes impractically so. Optimizations aren’t necessarily bad, so long as there is transparency about the tradeoffs or compromises made to achieve the gains, and a means to manage them.

An example is the recent Ronin Network hack. Ronin was an Ethereum side chain developed by Sky Mavis, creators of Axie Infinity, one of the most popular Web3 games. Ronin was a blockchain designed to support faster transactions at scale as the number of Axie Infinity players grew. Sky Mavis prioritized scale and speed over Byzantine fault tolerance; Ronin had its own consensus algorithm and only nine validator nodes. Unfortunately, this optimization came at a steep price — an attacker successfully acquired the private keys to five of the nine nodes, effectively gaining control of the quorum, and exploited this access to withdraw $625m in Ethereum over 6 days.

#3: Decentralization Means More Responsibility, Not Less

This seems to be a misconception about decentralization in general — if no one is “in charge” of P2P networks, that means all participants are absolved of any responsibility. Unfortunately it’s almost the opposite of the truth; decentralization increases each individual participant’s obligations.

Transacting on a network with no middleman or hierarchies to charge fees sounds like a great deal and in many ways it is. Decentralization can result in greater resiliency, as there is no central point of failure. Trustless networks can enable us to perform consensus without the need to know or trust the parties you transact with.

However, a decentralized system shifts many burdens and complexities to the end user. At the very least, users have to properly secure and protect their private keys. Users have to arrange for their own storage solutions as well as proving and protecting their identity with no support (discussed in greater detail below). Users might also end up being classified as a crypto business and thereby subject to privacy laws and even audits.

There’s a reason we’ve come to rely heavily on banks and other intermediaries: they abstract away many of these complexities for us. P2P is great as long as you’re willing to accept the responsibilities and manage the challenges that come with it — don’t expect a 1-800 number to call when something goes wrong.

#4: It’s Not Private

Blockchains do not inherently provide privacy. In fact, for public blockchains, it’s the opposite. Adding privacy on top of a public blockchain is possible, but difficult.

Cryptocurrency transactions require the use of a wallet address. A wallet address is a string of digits in a specific format that is recognized by the cryptocurrency’s network (e.g. Bitcoin or Ethereum) – so if you want someone to send you money, you have to make some of your information public, such as your wallet address and public key.

To gain access to the funds or tokens in a wallet address, the user must have the private key for the address; in fact having the private key is equivalent to having direct access to the funds in that wallet. This is an important difference between fiat transactions and cryptocurrency transactions. With fiat transactions, it is not possible to view a user’s bank account. In contrast, crypto transactions often involve sharing a wallet address to receive funds.

Each blockchain network such as Bitcoin and Ethereum has its own block explorer that provides data, including balances, of wallet addresses. Examples of block explorers are Blockchain.com for Bitcoin and Etherscan.io for Ethereum. This means that if a bad actor looks up the balance of a wallet address and also obtains the personally identifiable information (PII) of the address owner, the bad actor could threaten or harm the wallet owner in an effort to obtain the private key to assume control over the wallet and the funds.

The risk of physical harm or exposure to users can be mitigated if PII data is sufficiently protected (e.g. via a private blockchain), though these solutions often rely on more centralization. Conversely, it’s also easier for law enforcement to trace the use and lineage of funds by bad actors as a result of the public design and immutable transactions of blockchain systems.

#5: Encryption Can’t Be Treated As a Black Box

Paradoxically, one of the most common gaps in understanding in the crypto community is… cryptography. Cryptography is a complex field, and so it is somewhat understandable that vendors might hope to decouple these components and treat them as a black box. Unfortunately this strategy often results in security holes and may also unintentionally alienate potential customers.

In trustless networks, robust security comes from using a multi-pronged approach to encryption, which may include:

- asymmetric (aka public key) cryptography: these are the pairs of public and private keys described earlier. The sender uses the receiver’s public key to encrypt the message, which only the receiver (i.e. holder of the corresponding private key) should be able to decrypt.

- symmetric encryption: this uses a shared key between the sender and receiver, allowing them to encrypt and decrypt messages while impeding man-in-the-middle attacks.

- TLS and/or mTLS: TLS stands for transport layer security. It requires a sender or receiver (or both, in the case of mutual TLS or mTLS) to authenticate as a counterparty to create a connection for exchanging messages. TLS connections require certificates granted by a certificate authority and leverage public key cryptography in the authentication process.

For each of the above, it’s important to understand the actual cryptographic algorithms and underlying mechanisms; implementation choices matter a lot, and can even have impacts on who will be allowed to use your products, since encryption laws and approved algorithms vary by country. Other choices, such as using protocol buffers and mTLS rather than a RESTful API, will provide enhanced security but may require additional client-side support since they are not as common. Finally, as discussed in the next section, crypto vendors must be prepared to encrypt data not only in flight but also at rest.

#6: Data Storage Is Not A Solved Problem

Stemming from its P2P design, data storage is an open problem in blockchain systems. With no centralized party in charge of storing data (or paying for that storage!), these problems are often passed along to end users to deal with.

Blockchain networks are designed to validate and append transactions, and each node in the network must persist a record of every translation ever made. Each time a user buys, sells, or uses a virtual asset, they are effectively buying blockspace on a chain and using it to add a new record to the ledger. Adding new records makes the chain longer and longer, which means more and more data must be stored.

Moreover, for some transactions, there is often additional sensitive data such as PII that needs to be shared for compliance, legal, or technical purposes. This data is not optimized for blockspace and, due to the public and immutable design of blockchains, should not be stored on a blockchain. So, in those instances where relevant or required off-chain data must be shared, retained, and/or associated with a blockchain transaction, how should it be stored and retained? Moreover, how can you trust the counterparty to securely store the data? In our work with TRISA, we have employed encrypted Secure Envelopes, which have several advantages, but still don’t solve for the possible proliferation of PII.

Conclusion

While cryptocurrency has been around for more than a decade, vendors and engineering teams are still at the very early stages of developing around crypto. Tensions between performance and fault-tolerance, tradeoffs between the draw of decentralization and the convenience of having centralized decision-makers and blame-takers, and balancing acts between the varying laws and policies of countries around the world add up to a very complex and challenging space. We hope this post and others like it will encourage more thoughtfulness on the part of developers and consumers alike, and lead to more cohesive best practices around performance, privacy, security, and storage for crypto in the future.

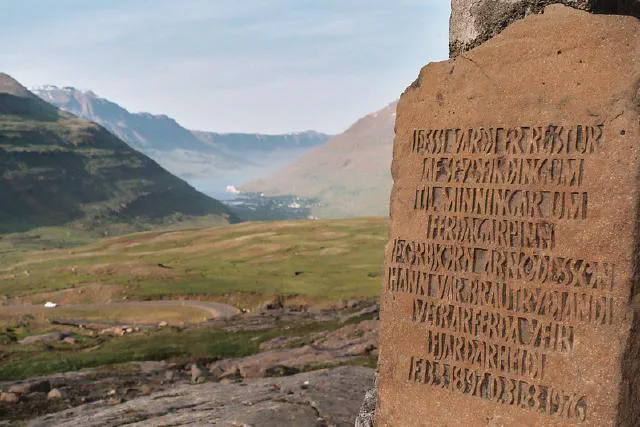

Photo by Victor Montol on Flickr Commons