Every time I’m writing complex rules in my code, I remember there’s a machine learning technique for this: Reinforcement Learning. RL models are able to learn the optimal rules given predefined rewards. Read on to learn how!

Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning is a branch of machine learning where the goal is to train an intelligent agent to take actions in an environment in order to maximize a “reward”. RL has famously been used to defeat the best human players in Go (the board game, not the programming language), but the approach is generic enough to extend to domains beyond gaming (robotics, natural language processing, etc.).

In this post we will explore creating a RL agent of our own to play Tetris. If you just want the code, you can check out the repo here.

Prerequisites

This is a Python project with some dependencies:

- gymnasium, a RL framework from OpenAI, the makers of ChatGPT

- stable-baselines3, a Python library with several implemented RL algorithms

- pyensign, the Ensign Python SDK so we can store and retrieve trained models

- pyboy, a handy GameBoy emulator for Python

- numpy and pandas, Python ML staples

- python-ulid, because sortable IDs are nice

Going to the Gym

To build our agent we will use gymnasium, an open source (MIT License) Python package from the same organization behind ChatGPT.

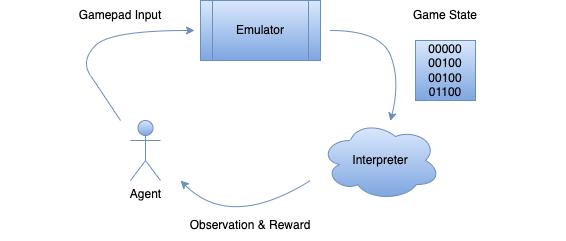

Our training loop will look something like this:

At each step the agent takes an action from the available action space {A, B, Up, Down, Left, Right, Pass} and makes an input to the emulator where the game is running. Then the agent receives a representation of the game state along with the reward for taking the action. The goal is to incentivize the agent to take actions that yield the best cumulative reward over time.

Note that unlike supervised learning, we don’t need any labeled data. In fact, we’ll be training the agent to play Tetris without telling it the “rules” of the game or how to score points!

We can create a custom TetrisEnv that subclasses gymnasium.Env and implements the following methods: reset(), step(), render().

reset

Reset the state of the game to the initial state. This is called at the beginning of each “episode” (e.g. when the board gets filled and it’s game over). We also introduce some randomness here to ensure that the agent explores more possible states of the game and it doesn’t get accidentally optimize for one scenario.

def reset(self, seed=None):

super().reset(seed=seed)

# Load the initial state

if self.init_state != "":

with open(self.init_state, "rb") as f:

self.pyboy.load_state(f)

# Randomize the game state

if seed is not None:

for _ in range(seed % 60):

self.pyboy.tick()

observation = self.render()

self.current_score = self.get_total_score(observation)

self.board = observation

return observation, {}

render

Render defines what the current observable state of the game is. In this method we extract a simplified version of the board as a multi-dimensional numpy array so that the model has something to work with.

def render(self):

# Render the sprite map on the backgound

background = np.asarray(self.manager.tilemap_background()[2:12, 0:18])

self.observation = np.where(background == 47, 0, 1)

# Find all tile indexes for the current tetromino

sprite_indexes = self.manager.sprite_by_tile_identifier(self.sprite_tiles, on_screen=False)

for sprite_tiles in sprite_indexes:

for sprite_idx in sprite_tiles:

sprite = self.manager.sprite(sprite_idx)

tile_x = (sprite.x // 8) - 2

tile_y = sprite.y // 8

if tile_x < self.output_shape[1] and tile_y < self.output_shape[0]:

self.observation[tile_y, tile_x] = 1

logging.debug("Board State:\n{}".format(self.observation))

return self.observation

step

Step is called to advance the state of the game once step by applying a button press (or sometimes no button press). It needs to return the current state of the board and also the reward for taking the action. To start, we will give out a positive reward for an action that increases the in-game score and a massive negative reward for reaching the “Game Over” state.

def step(self, action):

self.do_input(self.valid_actions[action])

observation = self.render()

if observation[0].sum() >= len(observation[0]):

# Game over

return observation, -100, True, False, {}

# Set reward equal to difference between current and previous score

total_score = self.get_total_score(observation)

reward = total_score - self.current_score

self.current_score = total_score

self.board = observation

logging.debug("Total Score: {}".format(total_score))

logging.debug("Reward: {}".format(reward))

return observation, reward, False, False, {}

Tracking Training Runs

When training machine learning models it’s often necessary to keep tabs on how the training is progressing. The stable_baselines3 library has an interface for creating custom log writers, so why don’t we create an Ensign writer? When the write method is called, it will publish an Event to an Ensign topic, similar to writing a log event to a file on disk.

import json

import asyncio

import logging

import numpy as np

from pyensign.events import Event

from stable_baselines3.common.logger import KVWriter, filter_excluded_keys

class EnsignWriter(KVWriter):

"""

EnsignWriter subclasses the Stable Baselines3 KVWriter class to write key-value pairs to Ensign.

"""

def __init__(self, ensign, topic="agent-training", agent_id=None):

super().__init__()

self.ensign = ensign

self.topic = topic

self.version = "0.1.0"

self.agent_id = agent_id

async def publish(self, event):

"""

One-off publish to Ensign.

"""

await self.ensign.publish(self.topic, event)

try:

await self.ensign.flush()

except asyncio.TimeoutError:

logging.warning("Timeout exceeded while flushing Ensign writer.")

def write(self, key_values, key_excluded, step=0):

"""

Write the key-value pairs to Ensign.

"""

meta = {"step": step}

if self.agent_id:

meta["agent_id"] = str(self.agent_id)

key_values = filter_excluded_keys(key_values, key_excluded, "ensign")

for key, value in key_values.items():

# JSON doesn't support numpy types

if isinstance(value, np.float32):

key_values[key] = float(value)

event = Event(json.dumps(key_values).encode("utf-8"), mimetype="application/json", schema_name="training_log", schema_version=self.version, meta={"agent_id": str(self.agent_id), "step_number": str(step)})

# Invoke publish in the appropriate event loop

publish = self.publish(event)

try:

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

except RuntimeError:

asyncio.run(publish)

return

asyncio.run_coroutine_threadsafe(publish, loop)

def close(self):

"""

Close the Ensign writer.

"""

asyncio.run(self.ensign.close())

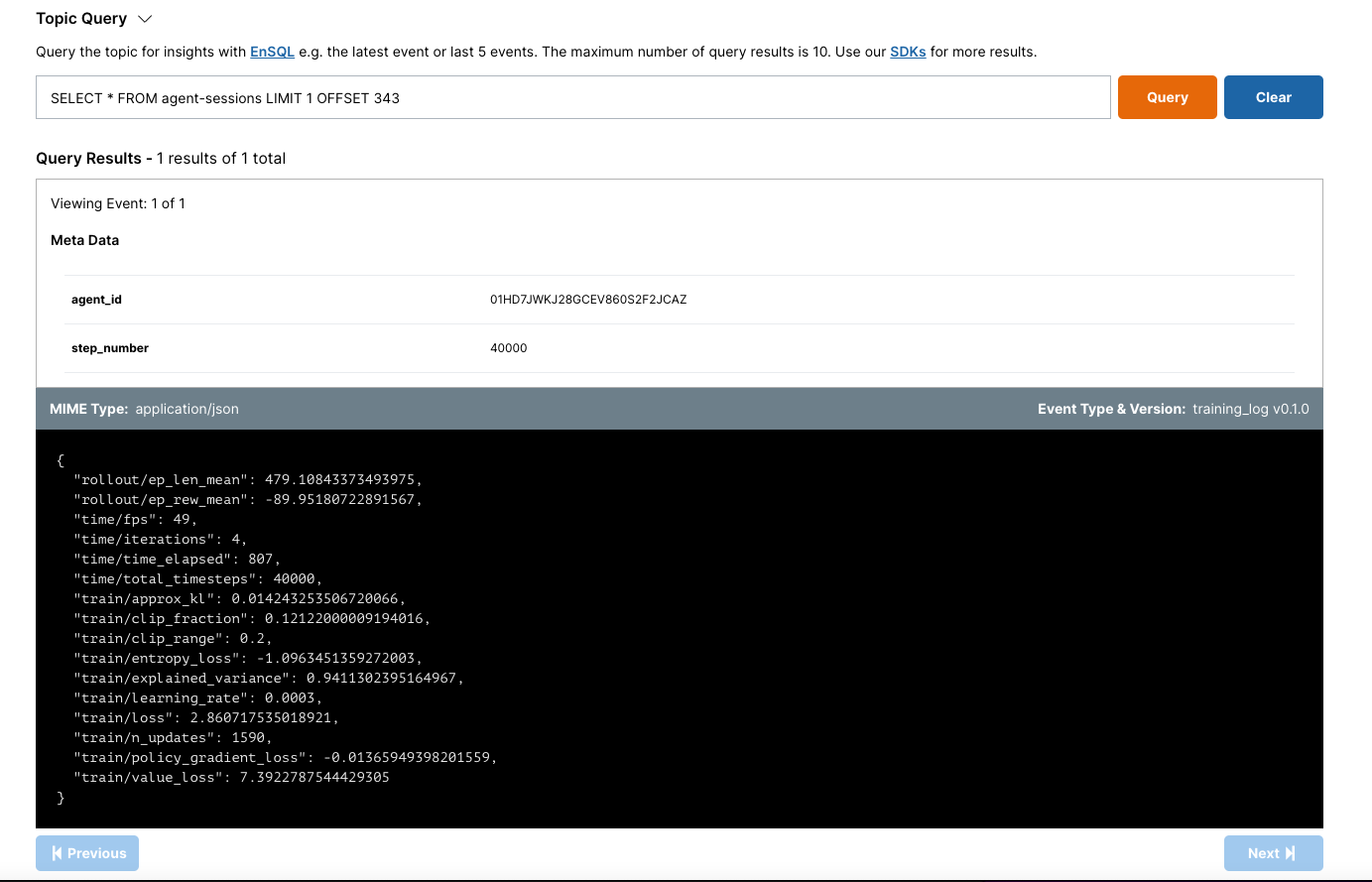

The cool part is that this lets us inject our own metadata tags which we can query on later. In the Ensign topic dashboard, we will be able to lookup previous training sessions to quantify training progress.

Starting the Training

Now that we have a RL environment setup, it’s time to train some models! Since we will probably be experimenting with different types of models is usually helpful to create a generic “trainer” class.

import io

import os

import asyncio

from datetime import datetime

import numpy as np

from ulid import ULID

import stable_baselines3

from pyensign.events import Event

class AgentTrainer:

"""

AgentTrainer can train and evaluate an agent for a reinforcement learning task.

"""

def __init__(self, ensign=None, model_topic="agent-models", model_dir="", agent_id=ULID()):

self.ensign = ensign

self.model_topic = model_topic

self.agent_id = agent_id

self.model_dir = model_dir

async def train(self, model, sessions=40, runs_per_session=4, model_version="0.1.0"):

"""

Train the agent for the specified number of steps.

"""

model_name = model.__class__.__name__

policy_name = model.policy.__class__.__name__

if self.ensign:

await self.ensign.ensure_topic_exists(self.model_topic)

if self.model_dir:

os.makedirs(self.model_dir, exist_ok=True)

# Train for the number of sessions

for _ in range(sessions):

session_start = datetime.now()

model.learn(total_timesteps=model.n_steps * runs_per_session)

session_end = datetime.now()

duration = session_end - session_start

# Ensure that async loggers have a chance to run

await asyncio.sleep(5)

# Save the model

if self.ensign:

buffer = io.BytesIO()

model.save(buffer)

model_event = Event(buffer.getvalue(), "application/octet-stream", schema_name=model_name, schema_version=model_version, meta={"agent_id": str(self.agent_id), "model": model_name, "policy": policy_name, "trained_at": session_end.isoformat(), "train_seconds": str(duration.total_seconds())})

await self.ensign.publish(self.model_topic, model_event)

if self.model_dir:

model.save(os.path.join(self.model_dir, "{}_{}.zip".format(model_name, session_end.strftime("%Y%m%d-%H%M%S"))))

if self.ensign:

await self.ensign.flush()

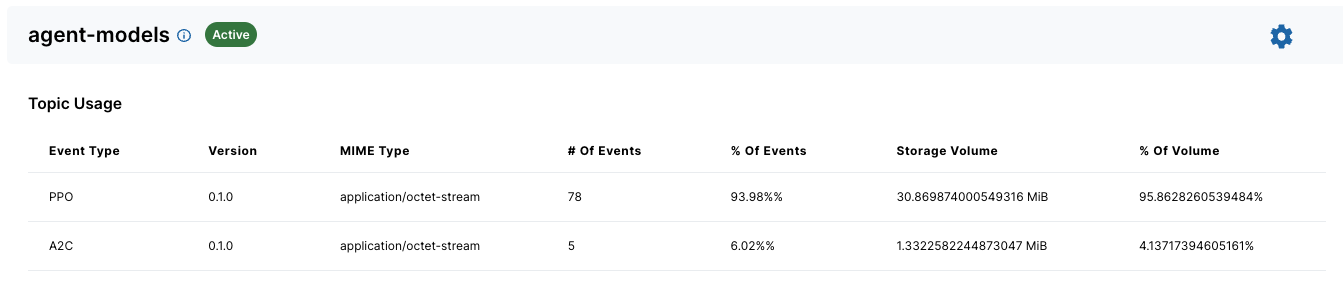

Storing the models in Ensign gives us a convenient way to checkpoint the model at the end of each session. Note that we are including the model name and version as part of the event schema which allows us to keep track of which models we’ve trained.

At this point we can kick off the training with a PPO model from the stable_baselines3 library.

import asyncio

import argparse

from ulid import ULID

from stable_baselines3 import PPO

from pyensign.ensign import Ensign

from stable_baselines3.common.logger import Logger, make_output_format

from agent import AgentTrainer

from writer import EnsignWriter

from tetris_env import TetrisEnv

def parse_args():

# Parse the command line arguments

...

async def train(args):

# Create Ensign client

ensign = Ensign(cred_path=args.creds)

# Configure the environment, model, and trainer

agent_id = ULID()

env = TetrisEnv(gb_path=args.rom, action_freq=args.freq, speedup=args.speedup, init_state=args.init, log_level=args.log_level, window="headless")

trainer = AgentTrainer(ensign=ensign, model_topic=args.model_topic, agent_id=agent_id)

model = PPO(args.policy, env, verbose=1, n_steps=args.steps, batch_size=args.batch_size, n_epochs=args.epochs, gamma=args.gamma)

# Set logging outputs

output_formats = []

if args.log_stdout:

output_formats.append(make_output_format("stdout", "sessions"))

if args.session_topic:

writer = EnsignWriter(ensign, topic=args.session_topic, agent_id=agent_id)

output_formats.append(writer)

model.set_logger(Logger(None, output_formats=output_formats))

await trainer.train(model, sessions=args.sessions, runs_per_session=args.runs)

await ensign.close()

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(train(parse_args()))

Evaluation

Now that all our models are in Ensign, it’s possible to evaluate any iteration of the PP0 model against a baseline. For example, if we want to evaluate the latest PP0 model we can use a pyensign query to retrieve it.

# Get the most recent model for the schema

model_events = await ensign.query("SELECT * FROM agent-models.PP0").fetchall()

model = model_events[-1]

# Deserialize the model from the event

buffer = io.BytesIO(model.data)

model_class = getattr(stable_baselines3, model.meta["model"])

model = model_class.load(buffer)

# Run the model in the environment

for _ in range(runs):

seed = np.random.randint(0, 100000)

obs, _ = env.reset(seed=seed)

terminated = False

steps = 0

while not terminated:

action, _states = model.predict(obs, deterministic=True)

obs, reward, terminated, _, _ = env.step(action)

env.render()

steps += 1

print("{}: Seed: {}, Steps: {}, Score: {}".format(schema, seed, steps, env.get_score()))

The random baseline model never manages to score points. After training the PPO model for ~1.6 million steps, it actually starts to complete some lines. Also, on average it survives longer than the random model. I think we can declare victory!

| Baseline | PPO Model |

|---|---|

|  |

Using model PPO v0.1.0

Baseline: Seed: 21523, Steps: 486, Score: 0

PPO v0.1.0: Seed: 21523, Steps: 518, Score: 0

Baseline: Seed: 96145, Steps: 328, Score: 0

PPO v0.1.0: Seed: 96145, Steps: 496, Score: 0

Baseline: Seed: 96558, Steps: 315, Score: 0

PPO v0.1.0: Seed: 96558, Steps: 532, Score: 0

Baseline: Seed: 80284, Steps: 308, Score: 0

PPO v0.1.0: Seed: 80284, Steps: 554, Score: 64

Baseline: Seed: 40057, Steps: 374, Score: 0

PPO v0.1.0: Seed: 40057, Steps: 524, Score: 64

Baseline: Seed: 80484, Steps: 486, Score: 0

PPO v0.1.0: Seed: 80484, Steps: 589, Score: 64

What Next?

So, if you’re looking for clever ways to automate decision making at work, don’t forget about reinforcement learning! Just like Tetris, it might take a bit of practice to get the hang of. But once you’ve added RL to your toolkit, you’ll see that it’s a much more flexible (and often less bug-prone) method compared to manually writing out a ton rules in your code. Even better, RL can uncover novel insights that supervised machine learning models cannot, thanks to tricks like the explore/exploit algorithm.

The best way to get good at RL? Get some practice objectively defining your reward (or punishment), and experiment with different policies and algorithms. Using the RL framework in our Tetris example, you should be able to do that a lot more quickly!

Here are some things you could try next:

- Experiment with different RL models and policies

- Create a more nuanced reward function that rewards shorter-term actions (e.g. minimize the number of “holes” in the board)

- Parallelize the training to explore the decision space

Note that since each agent has a unique ID, training multiple agents at once is not a problem since we can always query on the agent ID in the metadata tags.

Credits

This post is heavily inspired by the repo here which tackles a much more complicated game environment!

Photo by Ravi Palwe on Unsplash