Event-driven architectures (EDA) are enjoying a resurgence in interest due to many organizations’ need to accelerate rapid prototyping and get by with smaller, more cross-functional teams. In this post, we’ll demonstrate how to get started prototyping EDAs with the open source package Watermill.

Event-driven architecture is a powerful framework for building modern applications. Unlike conventional applications, which follow a request-response pattern, EDA enables the decoupling of software components, allowing them to asynchronously pass data between each other. EDA often helps reduce latency and increase throughput and is well suited for modern, distributed system architectures. It also opens up opportunities for organizations to build more responsive applications and more quickly integrate new features.

Eventing is Hard, Watermill Makes it a Little Easier

While there are many ways to build event-driven applications (check out this post to learn more about the types of tools available), building event-driven applications is still pretty hard. It requires advanced software engineering skills and DevOps skills to get projects up and running. On top of that, there is a lack of standardization among tools, so it is difficult to make changes to tooling after the fact (e.g. once a team has a better understanding of the throughput/latency needs of their app).

This is where Watermill comes in. Watermill is an open source Golang package that enables developers unfamiliar with EDA to get started building event-driven applications. Furthermore, it provides a standardized API that allows developers to experiment with different EDA tools. It is very simple to start building applications in one eventing tool, and with just a few changes, switch to another. The goal of Watermill, as the creators have stated, is “to make communication with messages as easy to use as HTTP routers.” They go on to say:

Just like you don’t need to know the whole TCP stack to create a HTTP REST server, you shouldn’t need to study all of this knowledge to start with building message-driven applications.

The Basics of Eventing

At the core of EDA is the event (or message), for example, a customer adding an item to a shopping cart or a smart light being turned on. In the EDA framework, a producer (or publisher) writes these events to a topic, while a consumer (or subscriber) listens to the topic stream, consuming and processing messages as they arrive.

There are several advantages to this framework. First, the producer and consumer applications can be built independently of each other and the processing can be asynchronous. There is no need for blocking code execution as there is in a traditional request/response framework, where the client has to block until it gets a response from the server. Second, the producer application can simply send data in its raw form, and it is up to the consumer application to do the data transformations that is suited for its use case. This opens up the possibilities of having multiple consumers listening on the same topic to serve different business functions.

Getting Started with Watermill

Watermill provides a very simple interface to create a publisher and a subscriber. The following code snippets assume that watermill, ensign, and watermill-ensign have already been installed.

type Publisher interface {

Publish(topic string, messages ...*Message) error

Close() error

}

type Subscriber interface {

Subscribe(ctx context.Context, topic string) (<-chan *Message, error)

Close() error

}

Creating a new publisher or subscriber is also very straightforward. Here is an example of how you can add a new publisher using an event streaming platform of your choice through the Watermill API.

Let’s say you want to start with Kafka:

publisher, err := kafka.NewPublisher(

kafka.PublisherConfig{

Brokers: brokers,

Marshaler: kafka.DefaultMarshaler{},

},

logger,

)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

defer publisher.Close()

If you later want to test out another backend, it’s just a very minor code change thanks to the power of the Watermill API! Here’s the same example as above, but with Ensign, a new self-orchestrating eventing platform:

publisher, err := ensign.NewPublisher(

ensign.PublisherConfig{

Marshaler: marshaler,

},

logger,

)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

defer publisher.Close()

Here is how you can add a new subscriber with Kafka:

sub, err := kafka.NewSubscriber(

kafka.SubscriberConfig{

Brokers: brokers,

Unmarshaler: marshaler,

ConsumerGroup: consumerGroup,

},

logger,

)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

And here’s how you’d do it with Ensign:

sub, err := ensign.NewSubscriber(

ensign.SubscriberConfig{

Unmarshaler: marshaler,

},

logger,

)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

As you can see, it is fairly straightforward to get started! When you’re ready to dig in a bit deeper, Watermill offers more advanced functionalities such as retry logic, throttling, poison queue, and observability metrics through the use of a component called router.

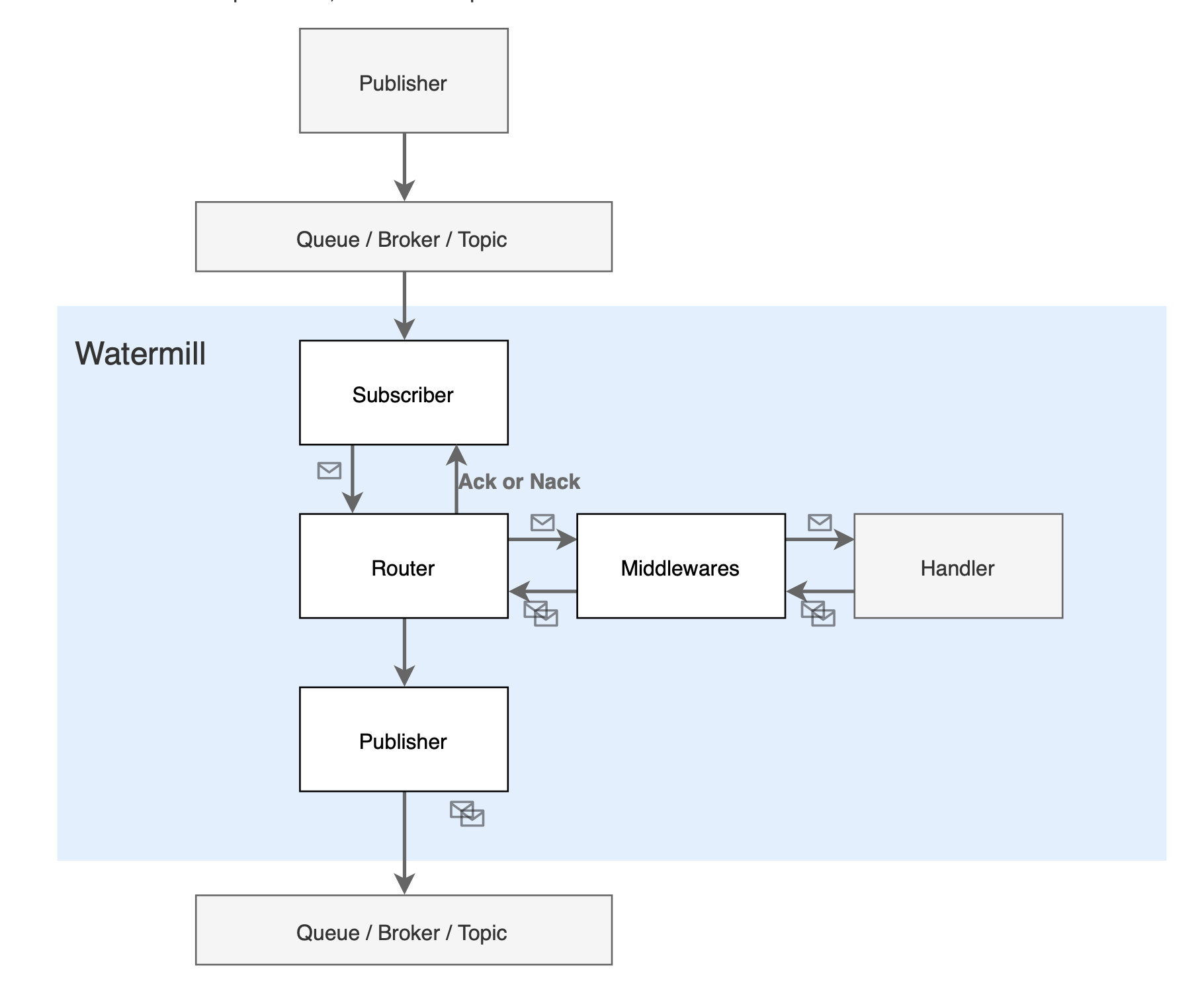

The following flowchart shows how the router can be used:

For those who have worked with HTTP requests, this probably looks familiar. The idea behind the router is that you can add any number of handlers that determine how to handle new messages that arrive on a topic. If you need to add more functionality to execute before or after the handler functions, Watermill has added middleware options, which are essentially decorator functions on top of the handler function. These middleware functions can be added to a specific handler or directly on the router to apply to every single message that is sent to the router.

The following is the function signature for a handler:

func (r *Router) AddHandler(

handlerName string,

subscribeTopic string,

subscriber Subscriber,

publishTopic string,

publisher Publisher,

handlerFunc HandlerFunc,

) *Handler

The handlerName is a unique value assigned to the handler. The handler receives the messages from the subscribeTopic and the handlerFunc is the function that gets executed by the subscriber when a new message arrives on the subscribeTopic. The handlerFunc returns new messages and puts them on the publishTopic. At this point, the publisher code gets executed. If there is no need for a publisher, then there is also an option to use a NoPublisherHandler where the handler only executes the subscriber function when a new message arrives in the subscribeTopic.

The function signature for a middleware is as follows:

type HandlerMiddleware func(h HandlerFunc) HandlerFunc

Watermill already comes with several middleware options which are available here but you can also build your own custom middleware and add it to the router. The following is an example where multiple middlewares are added to the router:

// Router level middleware are executed for every message sent to the router

router.AddMiddleware(

// CorrelationID will copy the correlation id from the incoming message's metadata to the produced messages

middleware.CorrelationID,

// The handler function is retried if it returns an error.

// After MaxRetries, the message is N'acked and it's up to the PubSub to resend it.

middleware.Retry{

MaxRetries: 3,

InitialInterval: time.Millisecond * 100,

Logger: logger,

}.Middleware,

// Recoverer handles panics from handlers.

// In this case, it passes them as errors to the Retry middleware.

middleware.Recoverer,

)

All Pros and No Cons?

With all of these building blocks, a Getting Started guide, and several examples in the Watermill repo to try out, it is very easy to get started building event-driven applications. So what’s the downside?

Watermill is not an eventing system itself, but rather provides a common API that can be used to interface with many differing underlying eventing backends (e.g. RabbitMQ, Kafka, Google PubSub, etc). As such, it does have limited functionality compared to the SDKs exposed directly by these backend eventing tools. But this is not a big setback, given that the purpose of Watermill is to enable teams to experiment and prototype architectures without having to go through the pains of setting up clusters and scaling up node resources. It’s nice to be able to focus on data flows, transformations, and application logic rather than editing tons of YAML files before you can even get started!

Want early access to a platform and community for developers building event-driven apps? Check out our free beta of Ensign.

Stay Tuned!

In the next blog post, I will cover an end-to-end use case using Watermill and Ensign, which like Watermill abstracts away much of the complexities of eventing so that you can focus on building more apps!

Photo by Terence Mangram on Flickr Commons