There’s no “best AI model for all use cases.” You have to do the science each time. If you’re new to experimental design for AI/ML, here’s a quick and dirty intro to the Model Selection Triple methodology.

What is the Model Selection Triple?

One of the most influential ideas in my early career and one that continues to guide how I think about building AI systems today comes from a 10-year-old paper published by an ancient (in tech years) ACM special interest group focused on large-scale data management problems and databases. That was probably not your first guess. Most people would probably guess it was the attention paper or the purple book or maybe the original proposal for scikit-learn.

But the paper that lives rent-free in my head is “Model selection management systems: The next frontier of advanced analytics,” by a group of researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Microsoft:

Model selection is iterative and exploratory because the space of [model selection triples] is usually infinite, and it is generally impossible for analysts to know a priori which [triple] will yield satisfactory accuracy and/or insights.

- Arun Kumar, Robert McCann, Jeffery Naughton and Jignesh Patel

This one line from this one paper is responsible for inspiring 80% of the Yellowbrick API. In order to understand the impact it had my career and the careers of tens of thousands of data scientists, and learn why it’s more relevant than ever in the age of AI, let’s first go back 10 years.

More Informed Machine Learning

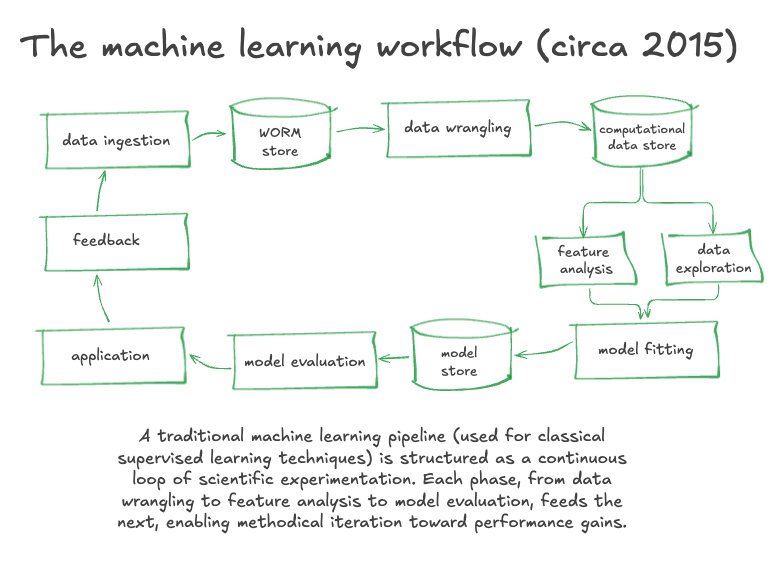

I gave my first big machine learning talk at PyCon 2016. I stood in front of an audience of hundreds of Python programmers and told them, voice shaking, that machine learning was getting easy but that it sucks to feel like you’re just taking shots in the dark when you’re using machine learning to do mission critical stuff. It hit a nerve.

Many people responded that they also felt like they were throwing spaghetti at a wall. As data scientists, the decision space before us was indeed, as Kumar et al describe in their paper, infinite. There were simply an infinite number of possible experiments that one could run.

“What’s your default

alphafor that model?” “How many trees did you use to get that F1 score?” “Oh I only use XGBoost.” “Can we do a dimensionality reduction to shrink the decision space?”

The big compute companies started offering SaaS tools for machine learning that allowed you to exhaustively and expensively grid search your hyperparameter space.

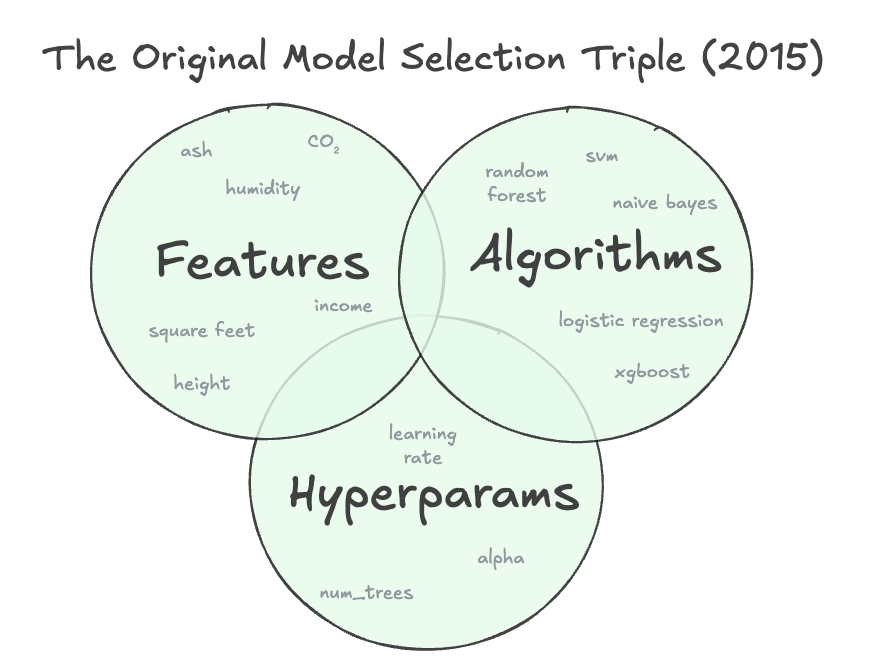

It felt like there must be a better, more methodical way for us as data scientists to traverse the decision space of the model selection process. And suddenly like an answer in the dark, Kumar et al’s paper was there to define our workflow in terms of model selection triples, meaning:

- algorithms (i.e. model architecture like SVM, random forest, neural net)

- features (i.e. data attributes extracted via your etl, wrangling, selection and engineering pipeline)

- hyperparameters (e.g. alphas, num_trees, learning rates, decision thresholds, etc)

This abstraction seems obvious now. It wasn’t then.

We took those ideas and put them into yellowbrick — an open source machine learning API that grouped machine learning diagnostic tools into sensible categories: tools that help you with algorithm comparison, tools that help you with feature selection, and tools that help you with hyperparameter tuning.

Quickly it started to feel like all of Data Science as a field was on the same page that the fastest path to the most optimal model for the problem you are trying to solve is to construct experiments where you would only vary one of {features, algo, params} at a time, and inspect the outcomes of those experiments so that you could be sure that you were trending towards accending the accuracy gradient (or descending the error gradient).

It really took off (and I guess some people still like it, nbd). (Note: Yellowbrick is now an Elder Data Science package and is not really being actively developed anymore.)

The Model Selection Triple Still Matters

In the age of AI, I sense we have lost the plot on principled experimentation a bit. I am watching people running around testing LLMs like proverbial beheaded chickens. This seems like a path to chaos and waste, not to mention a lot of unsatisfying experiments.

We still need methodology around AI implementation and instrumentation. In fact, you wouldn’t have a hard time convincing me that the original principles of machine learning are even more necessary than they were a decade ago when our models were stupider but easy to run on cheap compute.

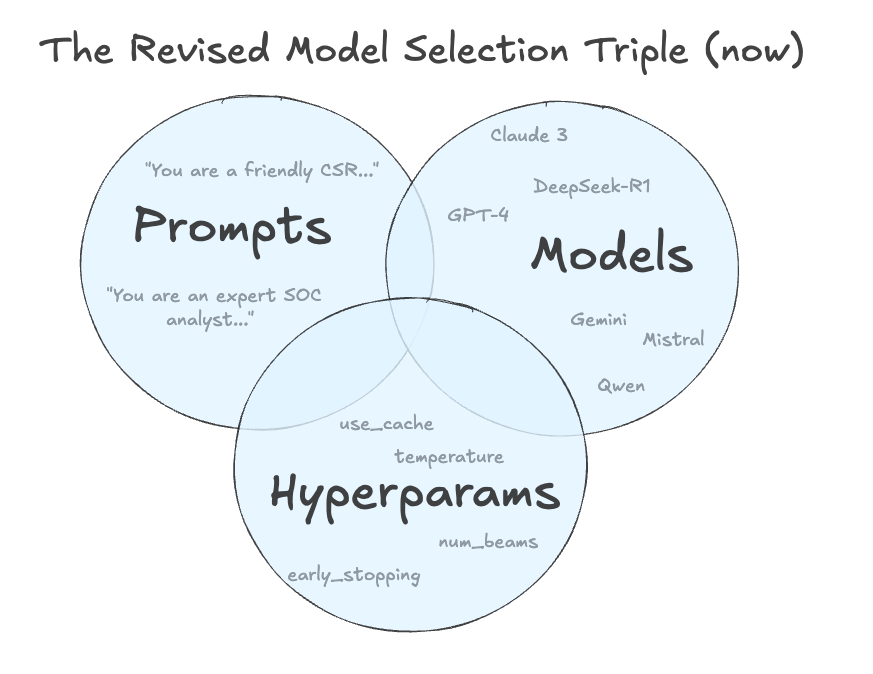

I believe the model selection triple (with a few minor refurbishments) can be extended to serve as an efficient and effective methodology for sciencing AI, i.e. for arriving at the best combination of {LLM, prompts, hyperparameters} to solve your specific problem as efficiently as possible. Let me attempt to convince you…

Prompts are the New Features

In classical machine learning, feature engineering is the layer where human insight is encoded into structured form to help models make sense of input. Think extracting n-grams, normalizing Unicode chars, stripping HTML, parsing timestamps, writing regex for phone numbers and mailing addresses. It is well-known in ML circles that this is where wrangling effort is most likely to be rewarded with real model lift.

In LLM development, prompts serve a similar role. They furnish context and shape how the model interprets the task. Prompt design in the new feature engineering. And just like traditional features, small variations (e.g. word order in an instruction, the addition of an example or a rubric) can yield different outputs.

Prompts need the same rigor as feature pipelines: they should be structured, versioned, tested, and refined.

Temperature, top-p, context length = new hyperparameters

Classical ML models have hyperparameters like max_depth, alpha, or num_trees that control how the model learns. With LLMs it’s similar; you can tune for creativity (or tune it out) using temperature and top-p, and toggle verbose mode using max tokens. These dials help with things like tone, completeness, factuality, stability, and other knobs of alignment.

Unfortunately hyperparameters don’t generalize well between tasks. A temperature that works for marketing copy might produce dangerously non-deterministic alerts for a cybersecurity workflow. You always have to tune, test, and interpret in context.

Also, keep in mind that you have access to more hyperparameters the closer you are to the source code. If you’re constructing LLM experiments via your cloud provider or using an OpenAI wrapper, you may get only the basic options. If you work directly with open weights (e.g., via HuggingFace), you can go deeper and adjust beam width, repetition penalty, presence frequency, and sampling strategies.

A Well-Structured LLM Experiment

A well-structured LLM experiment varies one factor at a time (prompt, model, or parameter) while holding the others constant. This allows you to isolate the effect of each change and add steering your AI experimentation workflows.

Here’s an example of a bad experiment:

You rewrite your System Prompt to be more formal and switch from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4. The model seems to improve. But which change helped?

Here’s a good experiment:

You run the same prompt and parameters across GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, log your observations, compare results, and prove that the cheaper model performs just as well.

To do well-defined experimentation you also need a stable reference to measure progress. This means investing in creating a fixed, versioned, and representative set of realistic inputs and their expected outputs (i.e. ideally in collaboration with SMEs at your organization). This lets you compare model behavior consistently across iterations. Even if the expected output isn’t deterministic, a well-curated test set helps you anchor decisions, identify regressions, and avoid cherry-picked outputs or lucky completions.

LLM Experiment Checklist

Here’s a short checklist of some of the key things that need to be in place for me to be confident in the validity of an LLM experiement:

- There is a clear problem statement

- We have an explicit hypothesis that records what we expect to happen and why

- There is one controlled variable (model, prompt, or parameter)

- We have a fixed test set for evaluation (inputs and expected outputs)

- We have defined success criteria (the more specific the better)

- We have consistent logging and versioning (prompt, model, parameters, output, metadata)

- We have documented the methods for reproducing the experiment (how would someone else re-run it?)

- We have evaluated the results using the test set to determine what has changed and what has stayed the same

Conclusion

LLM experimentation is still model selection, just with slightly different knobs. You need test cases. Prompt engineering needs to be methodical. Teams should track what they change in an AI pipeline and why. Evaluation needs to be treated objectively. Model performance should not be gauged with your gut. Work to come up with objective measures of what “good” looks like for your use case. Anchor each experiment with a clear hypothesis.

Rigor isn’t the enemy of speed. It’s how you avoid wasting time and money. Rushing leads to wasted compute, ambiguous results, and inconsistent outcomes. If you want to win at AI, treat experimentation as a science, not a gold rush.

My team specializes in bringing structure and velocity to AI experimentation. If you’re building something high-stakes and proprietary, I’d love to talk.

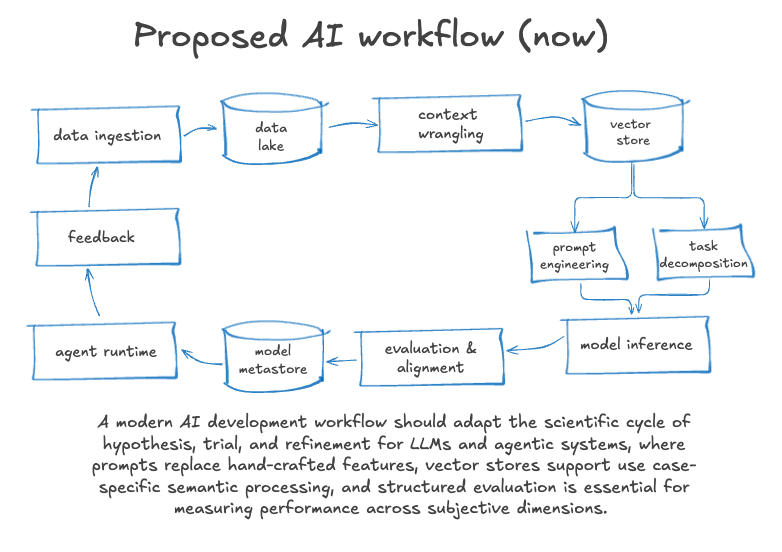

Photo generated using GPT-4o and some creative human prompting.