In the age of microservices and containerized applications, software is less monolithic and more interdependent. How do we write tests which account for this new reality? One common strategy is to create mocks for services. In this post, we’ll explore some of the challenges with testing in Go and dive into some concrete examples where creating mocks can help alleviate these problems.

Testing An Existing Codebase

As developers we’d like to think that we’re following test-driven development or at least “development with tests”. However, sometimes things need to be built quickly or we find ourselves inheriting an existing codebase. How do we write tests without fundamentally changing the source code?

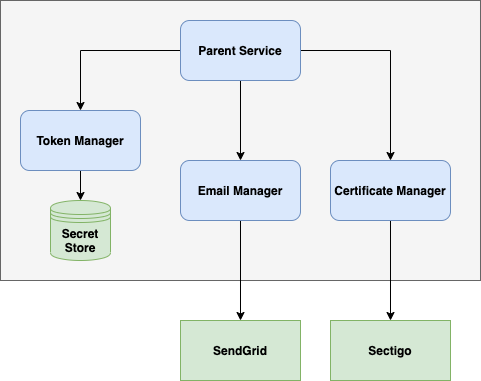

At Rotational we are interested in building intelligent distributed systems. This adds an additional layer to our testing problem because such projects often involve many dependencies. Consider for example an application that enables decentralized exchange of cryptographic information, which might require external calls to email delivery services and certificate authorities as well as internal calls to token managers, such as the one in the sketch below.

A common strategy for dealing with these dependencies is to use mocks. From a black box perspective a mock imitates the behavior of a service. We use a very generic definition of a service here; in reality it could be an internal or external API, a web server, an external process, or maybe even just a method. At the end of the day we want to be able to test that our code handles the possible scenarios that such a service introduces.

Go Forth And Mock

In languages like Python, adding unit tests to existing code is fairly straightforward, mostly due to the availability of third party libraries such as pytest. In addition, the weakly typed nature of Python lends itself to easy mocking. For example, the unittest.mock library can be used to replace method calls with calls that return mocked responses (e.g., 200 OK responses to HTTP requests).

This is in stark constrast with Go, which has some properties which make it more of a challenge to write effective tests. Go is strongly typed, which makes it impossible to swap out variables and methods for mocked types on the fly. In addition, Go makes an important distinction between exported and unexported variables, an analogue to public and private variables in other languages. While this design is useful for protecting variables from unwanted access, it also makes tests more difficult to implement since they usually exist in separate packages from the source code.

Nevertheless, Go is a popular language for distributed systems and sometimes we need a way to mock things to enable testing. Thankfully, it’s possible to create mocks with some effort.

Suppose we have an EmailManager1 struct with an associated method that’s responsible for sending emails using the SendGrid service.

type EmailConfig struct {

SendGridAPIKey string

}

type EmailManager struct {

client sendgrid.Client

}

func New(conf EmailConfig) *EmailManager {

return &EmailManager{

client: sendgrid.NewSendClient(conf.SendGridAPIKey),

}

}

func (m *EmailManager) SendEmail(message *mail.SGMailV3) (err error) {

var rep *rest.Response

if rep, err = m.client.Send(message); err != nil {

return err

}

if rep.StatusCode < 200 || rep.StatusCode >= 300 {

return errors.New(rep.Body)

}

return nil

}

We want to test that the SendEmail method is correctly interacting with the SendGrid API. One option for testing the success path is to give SendGrid a real API key and an email address designated for testing. However, this complicates our testing devops and creates an external testing dependency on SendGrid. A more attractive option might be to mock the behavior of the SendGrid client entirely in code2. This would have the benefit of allowing us to test the success path without the extra configuration or dependency headaches.

type mockSendGridClient struct{}

func (c *mockSendGridClient) Send(message *mail.SGMailV3) (rep *rest.Response, err error) {

return &rest.Response{StatusCode: http.StatusOK}, nil

}

Now that we have a mock that returns a successful REST response, all we need to do is swap the real SendGrid client out for the mock during the test. We can utilize a Go interface to accomplish this.

type EmailManager struct {

client EmailClient

}

type EmailClient interface {

Send(email *sgmail.SGMailV3) (*rest.Response, error)

}

What we’ve done here is defined a generic EmailClient interface which defines a Send function. Since our mockSendGridClient and the real sendGrid.Client both implement this function, this allows us to set EmailManager.client to an instance of either of them depending on if we are testing or in production.

There is one final complication to resolve. Since EmailManager.client is unexported, we won’t be able to reference it from the test package. One way to solve this is to push the problem onto configuration with a Testing flag.

type EmailConfig struct {

SendGridAPIKey string

}

func New(conf config.EmailConfig) (m *EmailManager) {

m = &EmailManager{conf: conf}

if conf.Testing {

m.client = &mockSendGridClient{}

} else {

m.client = sendgrid.NewSendClient(conf.SendGridAPIKey)

}

return m, nil

}

As we see below, this allows us to write a test which closely approximates reality, since the EmailCient is invoked and used the same way in testing and production, just with a different configuration.

func TestSendEmail(t *testing.T) {

message := mail.NewSingleEmail(

mail.NewEmail("sender", "emailtesting@rotational.io"),

VerifyContactRE,

mail.NewEmail("recipient", "emailtesting@rotational.io"),

"test email",

nil

)

conf := email.EmailConfig{

Testing: true,

}

em := emails.New(conf)

rep, err := em.SendEmail(message)

require.NoError(t, err)

require.Equal(http.StatusOK, rep.StatusCode)

}

When Is A Mock Not A Mock?

The email mock we’ve defined above is very barebones; it has the mimimum amount of code required to test the success path of SendEmail. Of course, the real SendGrid does a lot more than send back an HTTP response, since it has to marshal the email message into bytes, create the actual HTTP request, and wait for the response. This raises a bit of an existential question of what a mock is. Is it a method for bypassing code during tests or a full reimplementation of a service? Most of the time, we are interested in some middle ground between the two. For example, in the previous section we might have found it useful to add some simple validation to the mock, so that we can still catch error cases where we are creating badly formatted email messages (e.g, missing To or From addresses).

For most situations, reimplementing an entire service just so we can avoid the dependency and overhead of calling the real one is probably not worth our time. For example, services like the Sectigo Certificate Manager have extensive REST APIs and it would be difficult to handle all the edge cases. However, we may find it useful to define the mock3 as a test server which by default returns the “good” responses to all the endpoint calls.

type Server struct {

server *httptest.Server

router *gin.Engine

handlers map[string]gin.HandlerFunc

calls map[string]int

}

// New initializes a new server which mocks the Sectigo REST API.

func New() (s *Server, err error) {

gin.SetMode(gin.TestMode)

s = &Server{

handlers: make(map[string]gin.HandlerFunc),

router: gin.New(),

calls: make(map[string]int),

}

s.Handle(sectigo.AuthenticateEP, http.MethodPost, s.authenticate)

s.server = httptest.NewServer(s.router)

sectigo.SetBaseURL(s.URL())

return s, nil

}

// Close the test server to complete the tests and cleanup.

func (s *Server) Close() {

s.server.Close()

sectigo.ResetBaseURL()

}

// Handle is a helper function that adds a handler to the mock server's handlers map and

// returns that handler function when the endpoint is called.

func (s *Server) Handle(endpoint string, handler gin.HandlerFunc) error {

if _, ok := s.handlers[endpoint]; !ok {

return fmt.Errorf("unhandled endpoint %s", endpoint)

}

s.handlers[endpoint] = handler

return nil

}

// URL returns the URL of the test server.

func (s *Server) URL() *url.URL {

u, err := url.Parse(s.server.URL)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return u

}

// Handler for a "successful" authentication call.

func (s *Server) authenticate(c *gin.Context) {

var (

in *sectigo.AuthenticationRequest

access string

refresh string

err error

)

s.calls[sectigo.AuthenticateEP]++

if err = c.BindJSON(&in); err != nil {

c.JSON(http.StatusBadRequest, err)

return

}

if access, err = generateToken(); err != nil {

c.JSON(http.StatusInternalServerError, err)

return

}

if refresh, err = generateToken(); err != nil {

c.JSON(http.StatusInternalServerError, err)

return

}

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, §igo.AuthenticationReply{

AccessToken: access,

RefreshToken: refresh,

})

}

There are a few things going on here. We are using httptest and gin to quickly spin up a test server and configure an endpoint to our mocked authenticate handler. We also call the project-specific method sectigo.SetBaseURL to ensure that all the Sectigo requests get directed to our mock. In the mocked authenticate handler, we simply generate some valid-looking JWT tokens and send them back in the request so our Sectigo client code hits the “success” path. Finally, we have a call counter which helps verify that the correct endpoints are being called. This infrastructure enables us to write a simple test4 for our Sectigo client Authenticate method.

func TestAuthenticate(t *testing.T) {

m, err := mock.New()

require.NoError(t, err)

defer m.Close()

s.api, err = NewSectigoClient("foo", "supersecret")

require.NoError(t, err)

require.NoError(t, s.api.Authenticate())

}

What happens if we run into an edge case we want to add a test for? With the mock we’ve set up, this is actually pretty straightforward. For example, if we want to test that our Sectigo client is handling invalid credentials properly, we can replace the mock authenticate handler with one that has validation logic.

func TestAuthenticateInvalidCreds() {

m, err := mock.New()

require.NoError(t, err)

defer m.Close()

m.Handle(AuthenticateEP, func(c *gin.Context) {

var (

in *AuthenticationRequest

)

if err := c.BindJSON(&in); err != nil {

c.JSON(http.StatusBadRequest, err)

return

}

if in.Username != "foo" || in.Password != "supersecret" {

c.JSON(http.StatusUnauthorized, "invalid credentials")

return

}

c.JSON(http.StatusInternalServerError, "how did we get here?")

})

s.api, err = New("invalid", "invalid")

require.NoError(t, err)

err = s.api.Authenticate()

require.EqualError(t, err, ErrInvalidCredentials.Error())

}

Conclusion

Testing distributed systems applications is difficult due to the many interdependencies involved and the design of programming languages such as Go. In this post, we’ve looked at a few examples of how mocks can be used to alleviate some of these pain points.

Mocks can help us bypass code that we don’t want to run in our tests without fundamentally changing the architecture of our applications. With some configuration, mocks allow us to test both the success and error paths of our service-dependent code, enabling more complete unit testing, and a greater degree of confidence in the implemention of highly complex systems.

Photo by Dave Hoefler on Unsplash