Double-checked locking is a common mechanism to avoid race conditions when using read and write locks. Unfortunately, as with nearly all things related to concurrency, it is easy to get wrong or forget.

tl;dr If you’re just looking for an example in Go of double-checked locking, an example is below. Please note however that double-checked locking is not good for all systems and is sometimes considered an anti-pattern. Using other Go concurrency mechanisms like sync.Once can be a better choice, e.g. for Singleton design patterns.

type Store struct {

sync.RWMutex

values map[string]*rate.Limiter

}

func (s *Store) Get(client string) (limiter *rate.Limiter) {

// To prevent contention we want to use the RLock as much as possible.

s.RLock()

// First check if the rate limiter exists for the client.

var exists bool

if limiter, exists = s.values[client]; !exists {

// We need to obtain a write lock in order to create a limiter for the client.

// However, we need to unlock the read lock first to prevent a deadlock.

s.RUnlock()

s.Lock()

// Because another go routine could have acquired the lock between when we

// unlocked the read lock and acquired the write lock, we have to double check

// our condition or risk overwriting the limiter that is already created.

if limiter, exists = s.values[client]; !exists {

limiter = rate.NewLimiter(20, 120)

s.values[client] = limiter

}

// Unlock the write lock and return the limiter. Note we need to return in the

// if block at this point to prevent a second call to s.RUnlock.

s.Unlock()

return limiter

}

s.RUnlock()

return limiter

}

For more on the reasoning behind double-checked locking; read on!

Introduction

This is the first part in a series of posts about concurrency patterns in Go and like all good series, it comes from our real life experience of working on highly concurrent distributed systems like Ensign!

Consider the scenario where you would like a data structure to be synchronized between many go routines such that if a value does not exist in the data structure a go routine can add the value, but the value should not be overridden by other go routines. A good example of this is a cache, where you would like to store a value used by other go routines for a set amount of time before deleting it to prevent unbounded memory growth.

At the end of this post, we’ll show you our real world example that we created for rate limiting, but to illustrate the problem, let’s look at a simple example first.

The Problem

Consider the following Store, where we’d like to have go routines concurrently access values in a map that is rarely written to. In particular, the value of the map will only be set once if it does not exist, read a lot, then potentially deleted in the future.

Because most of our accesses are reads, using a sync.Mutex seems very heavy weight; it only allows one go routine access to the map at a time, no matter what key they are accessing. This could really slow down the performance of our program. To allow concurrent read access to the map we implement a sync.RWMutex as follows:

type Store struct {

sync.RWMutex

values map[string]int

}

// SetOnce sets the value to the key only if it doesn't already have a value. Returns

// true if the value was set (e.g. it did not exist already).

func (s *Store) SetOnce(key string, value int) bool {

s.RLock()

if _, exists := s.values[key]; !exists {

s.RUnlock()

s.set(key, value)

return true

}

s.RUnlock()

return false

}

func (s *Store) set(key string, value int) {

s.Lock()

defer s.Unlock()

s.values[key] = value

}

Sidenote: if the above is your usecase, consider using a sync.Map instead. However as the documentation suggests, depending on your access pattern, implementing double-checked locking might be better.

Unfortunately, the above implementation introduces a race condition. It is possible for two or more go routines to perform the check in the read-lock concurrently, detect that the value does not exist, then attempt to acquire the write lock. Go queues accessors to the write lock, therefore they will each acquire it one at a time, write their value and overwite the previous value set by the go routine.

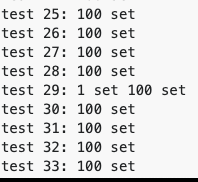

Try running the following example code on the Go playground a few times; you’ll notice that occasionally you’ll have two or more go routines who think they’ve set the value. If you don’t see it the first time, keep trying. You will notice that at least one of the tests has a situation where the value gets set more than once. See the screenshot below for an example. One of the reasons this error is so common is because the race condition is very hard to observe! To more clearly illustrate the point, you can also introduce some lag in the set function either by doing a computation before acquiring the lock or sleeping for a bit of time.

The Solution

To prevent the race from occurring, we want to ensure that only the first go routine to acquire the lock sets it. To do this, we need to double-check our initial existence condition to make sure it’s still true when we’ve acquired the write lock.

// SetOnce sets the value to the key only if it doesn't already have a value. Returns

// true if the value was set (e.g. it did not exist already).

func (s *Store) SetOnce(key string, value int) bool {

// Acquire the read lock and check if the value exists

s.RLock()

if _, exists := s.values[key]; !exists {

// Acquire a write lock to set the value

s.RUnlock()

s.Lock()

defer s.Unlock()

// Double-check that the condition isn't true and some other go routine didn't

// beat the caller to acquiring the write lock.

if _, exists := s.values[key]; !exists {

s.values[key] = value

return true

}

// Otherwise, don't overwrite the old value, but also make sure to return so

// that we don't call s.RUnlock twice accidentally in this function.

return false

}

s.RUnlock()

return false

}

Now you’re guaranteed that only one go routine will ever set the value. Note, however, that you can’t guarantee which go routine sets the value, just that whichever go routine acquires the write lock first will be the winner.

Here is example code on the Go playground that illustrates the semantic. Run the test multiple times and you will notice that the value gets set only once per test.

Rate Limiter Example

We have an API service that we want to prevent from being abused, so we’d like to rate limit it on a per-client basis. However, we also expect that we’ll have lots of clients, so we don’t want to store rate limit information for the duration of the service and we’d like to clean it up occasionally!

Determining if a client is violating rate limits can be done using the Golang rate package. However, we need some data structure to map clients by their ID or IP address to their specific limiter. Each request is handled by the API server in its own Go routine and we have another go routine that is routinely cleaning up all of our rate limiters to prevent unbounded growth.

Below is a much simplified version of our limiter solution (don’t directly copy and paste this code, it is for illustration purposes; but if you’re interested in a blog post about rate limiting, let us know!)

type ClientLimiter struct {

sync.RWMutex

clients map[string]*rate.Limiter

limit int

burst int

}

func NewClientLimiter(limit, burst int, cleanupInterval time.Duration) *ClientLimiter {

limiter := &ClientLimiter{

clients: make(map[string]*rate.Limiter),

limit: limit,

burst: burst,

}

// Start the limiter cleanup go routine

go limiter.cleanup(cleanupInterval)

return limiter

}

// Get or create a rate limiter for the specified client.

func (c *ClientLimiter) Get(client string) (limiter *rate.Limiter) {

c.RLock()

var exists bool

if limiter, exists = c.clients[client]; exists {

c.RUnlock()

return limiter

}

// Create the limiter with double-checked locking

c.RUnlock()

c.Lock()

defer c.Unlock()

if limiter, exists = c.clients[client]; exists {

return limiter

}

limiter = rate.NewLimiter(c.limit, c.burst)

c.clients[client] = limiter

return limiter

}

// Check if the client is allowed access, if false they've exceeded the rate limit.

func (c *ClientLimiter) Allow(client string) bool {

return c.Get(client).Allow()

}

// Periodically cleanup the limiters in the client

func (c *ClientLimiter) cleanup(interval time.Duration) {

ticker := time.NewTicker(interval)

for {

// NOTE: you probably want to do more here e.g. select on a stop channel or

// grab the timestamp from the ticker to remove limiters that haven't been used

// in a certain amount of time. This simplified implementation is brute force.

<-ticker.C

// double-checked locking, acquiring a lock for only one key at a time

for _, client := range s.clients {

c.Lock()

if _, exists := s.clients[client]; exists {

delete(s.clients[client])

}

c.Unlock()

}

}

}

Hopefully this real world example illustrates why double-checked locking might be a good concurrency pattern in some multi-threaded environments.

We’re looking to create a series on concurrency design patterns; stay tuned to the blog for more to come in the series!

Photo by Timothy Dykes on Unsplash