We spent three months testing two AI coding assistants across our team of six. So far we’ve learned that overdelegation backfires, well-scoped tasks help, and accelerating an individual ≠ accelerating a team.

Are AI Coding Assistants an Accelerator?

At the start of this year, our CTO challenged us all to try out some of the newly available AI coding tools. The promises of 10x productivity gains seemed like mostly marketing, but she wondered “could these tools accelerate us?”

In June, we formalized our investigation by asking everyone to select from one of two options (Cursor and/or Copilot; some agreed to test both, and one opted out) and participate in a 6-month study, covering sprints 14-26 of CY2025. We weren’t aiming for research-grade rigor but wanted to capture as much data as possible, including both quantitative and qualitative measures of productivity. At the end of the year, we plan to select one of the two tools to continue paying for based on the outcomes of the study.

Quantitative Measures

Our team uses Shortcut to track our sprints, so we have access to a lot of quantitative data. We know quantitative metrics can’t tell a complete story about the impact of AI tools on our productivity, but we already have years of data and knew it could serve as valuable context. We were particularly interested in the following measures:

- Individual velocity (measured as points completed per week per engineer) and individual throughput (measured as stories completed per week per engineer).

- Team velocity (total points completed per week as a team) and team throughput (total stories completed per week as a team)

- Mean velocity (total points completed per week, divided by engineers) and mean throughput (total stories completed per week, divided by engineers).

- Longitudinal data to help us understand how the above metrics compare to last year.

Some of our research questions included: will our weekly points increase? If so, is there any increase during the first week of the sprint where our burndown rate is slower? Will bug tickets increase or decrease (compared to feature stories and chores)?

Qualitative Measures

One new thing we started doing for this study was collecting qualitative data, in biweekly 30-minute interviews between each participating engineer and our technical project manager. Meetings like this are already a normal part of our sprint activities: an opportunity for everyone to plan for his or her upcoming sprint. The data collection portion follows a standard set of interview questions (see below).

- What was your biggest AI fail this week?

- What was your best AI success this week?

All interviews are captured and transcribed using the AI notetaking tool Fireflies.

Observations

We now find ourselves at the midway point of our investigation. So far the quantitative data is not conclusive, but it is interesting.

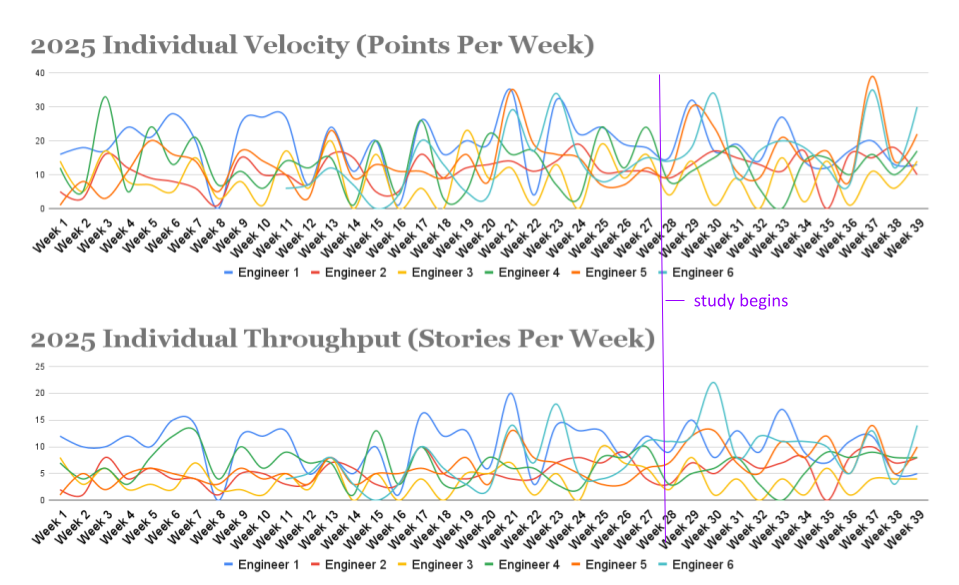

Two of our participating engineers (Engineer 5 and Engineer 6 in the graph above) joined our team in 2025, and for them, we have definitely observed individual acceleration over the course of the year. While we do not attribute all of this acceleration to AI coding tools, they are both AI power users, so we suspect the increase in their individual velocity (points per week) and throughput (stories per week) is not simply coincidence. However, neither individual velocity nor individual throughput has changed substantially for the four veteran engineers who are participating in our study.

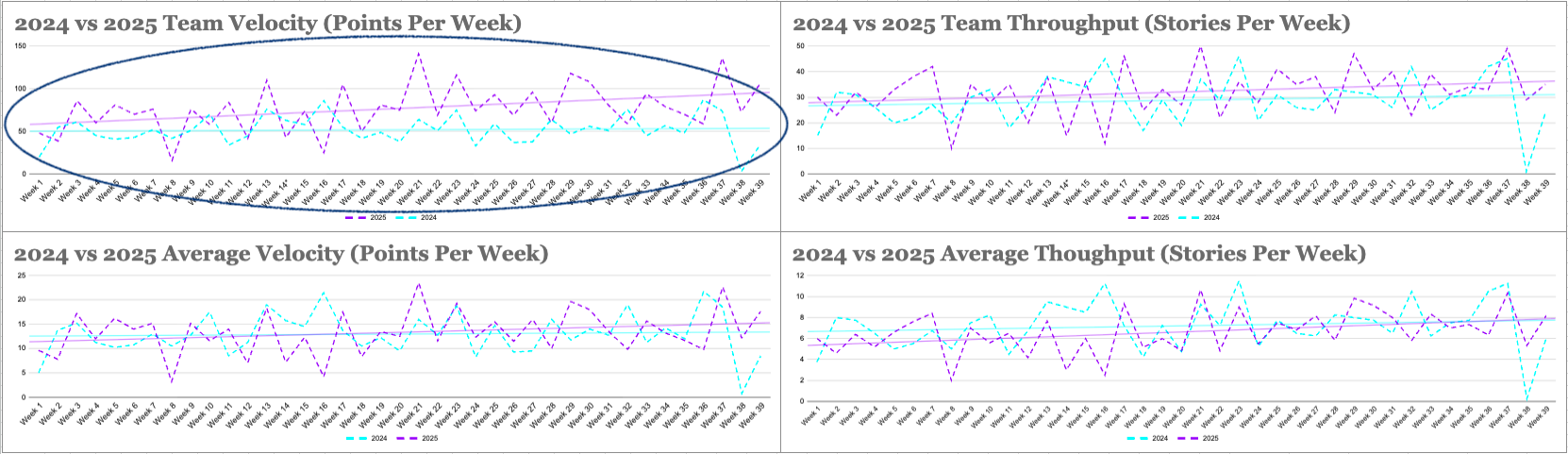

In the group of graphs below, we compare the metrics for the team across two years. The top lefthand shows an increase in our team velocity from 2024 to 2025 (i.e. how many points we finish as a group each week), though this increase is substantially less when we consider the lower lefthand graph, which shows a much smaller (but still noticeable) increase in average velocity from 2024 to 2025 (i.e. how many points we finish each week, divided by the number of engineers). This makes sense, since part of the “acceleration” we observe in the top lefthand chart is actually the result of growing our team, and thus, our capacity. Nonetheless, all four graphs have positive slopes.

The quantitative data we have captured so far seems to reinforce some of the patterns we have observed in the qualitative data (shared in the next section), namely that individual acceleration from AI use is meaningful but does not automatically lead to team acceleration.

Lesson One: Avoid the “Total Automation” Pattern

The first and most important thing we learned from our qualitative interviews was that our junior engineers started by delegating way too much responsibility to the AI coding tools, which backfired.

When asked about Sprint 14’s biggest failure, one junior engineer said, “Using Cursor for everything.” He’d initially been excited to use the tool until he’d asked a senior engineer for feedback on a small prototype he’d built with it, and got pushback. It turned out the “small prototype” consisted of thousands of lines of code. While our junior developers can now generate tons of code, this creates a bottleneck for senior reviewers who now need to understand not just what the code does, but whether the AI-driven choices around things like data accesses, manipulation, storage, and forecasting are sound.

This forced us to adapt. We added lines-of-code counters to our CI/CD pipelines to flag and discourage overly sweeping PRs. This helped keep merge requests manageable. The same junior engineer now says his biggest win so far has been “learning to use Cursor less to feel more productive,” focusing the tool specifically on debugging and unfamiliar APIs. Another teammate echoed this sentiment, developing what he called “a sustainable workflow” that balanced AI assistance with human judgment.

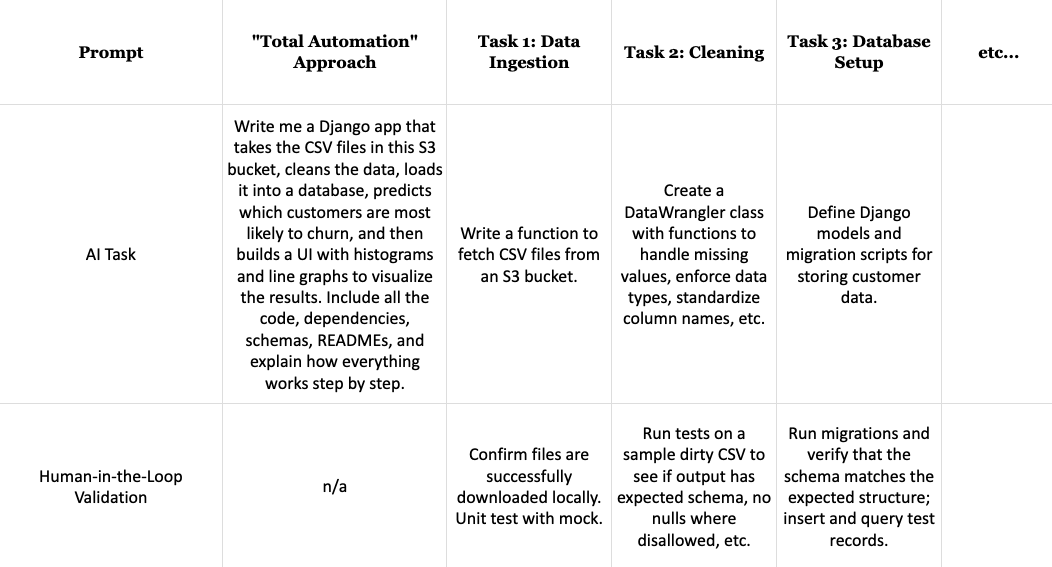

We found that the “total automation pattern” (see below) resulted in code that wasn’t compatible with our peer review processes. Our engineers did not like it when the AI took too much control: assistants inserted “improvements” that not only produced overly large PRs, but sometimes broke functionality or added bugs. Instead, we started to decompose GPU-bound work into more discrete tasks, with intentional human-in-the-loop validation measures after each step.

By Sprint 16, something interesting happened: team members began carving out specific niches where AI consistently excelled (story creation, PR reviews, routine data analysis tasks). We found the tools work best for our team when applied to well-defined, repetitive tasks rather than to things like architectural design (we’ll always remember the time the AI assistant delivered a prototype application that contained 50 databases).

Lesson Two: Riding the Reliability Rollercoaster

Two months into our study, a senior engineer spoke up about something we’d all felt but couldn’t quite articulate: using these tools day-to-day felt like “accountability whiplash.”

While some days everything was great, others were filled with 500 errors from overwhelmed servers. A prompt that worked yesterday would suddenly start returning dozens of bullet points instead of a tidy brief. You’d find your favorite GPT model and learn the next week that it had been deprecated (this happened more than once). There were also the elephants in everyone’s LinkedIn feed, the allegations against the builders of these tools, for misappropriating intellectual property. Several times we were alarmed to discover policies on user data retention and privacy (often buried in terms of service and obscure application settings) changing seemingly overnight.

The volatility of AI assistant performance (not to mention public confidence) led to fluctuating trust levels amongst our engineers. Could we even trust these tools? How do you maintain accountability when AI is unpredictable?

In response we have adopted a default position of skepticism. We do not assume model endpoints are always up, and we always have fallbacks. We are spending less and less time trying to control AI behavior through prompt engineering and more and more time developing APIs to scope and gate that behavior. We’re less likely to reach for MCP, which leaves more of the API up to the interpretation of an LLM. Instead we prefer more traditional RESTful interfaces that exchange well-defined, structured schema. We are willing to sacrifice some flexibility there in exchange for more predictability.

Lesson Three: Accelerating the Person vs the Team

Finally, our idea of what it means for AI to “accelerate” us has become more nuanced. Two months into our study, METR, a model evaluation think tank, published findings that AI assistants may actually decrease developer productivity.

And yet, our CEO (who is also participating in the study) rightly pointed out that the AI coding tools did seem to help with “the blank page problem.” Several of us have successfully incorporated AI assistants into our individual brainstorming processes. Our junior engineers have made good use of AI tools to overcome the initial paralysis of starting a new task significantly outside their comfort zone (e.g. using an unfamiliar programming language, learning a new web framework, etc).

The lesson we have learned about acceleration is that these tools reinforce a sense of individual solutionism, seemingly designed to accelerate a single person. Neither of the AI assistants we are testing seem to make collaboration easier. If anything, they make it harder to collaborate. So while they do make us more productive as individuals, our results are not always in harmony.

As a consequence, we have added more co-working time for our engineers, like whiteboard sessions and brainstorming conversations. We have to intentionally synchronize more often to maintain harmony and to ensure our individual contributions are non-overlapping and compatible.

What Actually Works (and What Doesn’t)

After three months of trial and error, some clear patterns have emerged. Here are some of the areas where we have observed the most successes and failures:

| AI Wins | AI Fails |

|---|---|

| Narrow tasks with specific scope | The “total automation” pattern |

| Prototyping and exploring unfamiliar APIs | Architectural decisions |

| Generating test cases and boilerplate code | Core business logic/domain expertise |

| Debugging and error identification | Writing documentation/release notes generation |

The Path Forward: Integration, Not Replacement

While we still have a few months left in our study, we’ve already learned a lot.

Probably most importantly, we’ve evolved from sandbox-style experimentation to more disciplined use. The development pattern that works best for us is to break problems down into tasks and create purpose-built AI tools to address those specific bottlenecks. Having a single mega prompt or tool that attempts to automate everything simply does not work.

As we greenlit our engineers to build custom AI tools and began to productionalize them, the patterns coalesced into a platform (we call it Endeavor) that we can all use for agentic testing and deployment. Importantly, Endeavor saves shared artifacts of each experiment (including Git-style prompt versioning, model selections, and resulting generations) so that they are accessible to the entire team.

We learned to be more skeptical about AI; rather than assuming an LLM can definitely do a task, we now use our internal platform to test whether it can, empirically. We now frontload more of the design process, defining earlier on what “success” would mean to an end user and what the stakes are for our business. Then we rigorously test whether the prompts and models are meeting those expectations.

Most importantly, we have learned that the biggest driver of productivity is leaning into human collaboration. While off-the-shelf tools are convenient, we needed a solution designed to accelerate us as a group, not just as individuals. The most valuable agents we’ve created so far address organizational friction points (e.g. helping us get from an unstructured brainstorming call to a set of clearly defined stories to pull into the next sprint). Looking ahead, we’ll be focused on tools that help us achieve more together than any one of us could alone, with or without AI.

Have suggestions for other ways we could crunch the numbers? Connect with us on LinkedIn!

Image generated using GPT-5