Contexts are a critical part of services implemented in Golang. Although we see them often in server interfaces, they can be mysterious to developers implementing request handlers. In this post, we’ll discuss what contexts are and take a look at a specific example where contexts shine: services that are implemented as a series of microservice requests. Then we’ll dive into the tl;dr of contexts — namely, the two crucial rules that all service handlers should implement. Finally, we’ll demonstrate a quick experiment using gRPC to show how context deadlines are propagated to downstream microservices during request processing, enabling effective coordination.

The code for the experiment can be found at: github.com/rotationalio/ctxms.

Contexts in Service Handlers

If you’ve implemented a gRPC API you’ll know that the RPC interface for a request handler has a function signature that looks something like:

func (s *Server) MyRPC(ctx context.Context in *Request) (out *Reply, err error) {}

The first argument is always a context.Context, which if you’re like me, you think of as “the thing with the deadline for the client”. However, if you’re also like me, 90% of the time you simply ignore it and implement the request handler without using that argument at all.

If most of the time, ignoring the context is fine, then what are contexts?

What are Contexts?

The context package in the Go standard library provides a type Context that contains request-scoped values and signals that are safe for simultaneous use by multiple go routines and which facilitates communication across API boundaries and between processes.

So what should you do with the context? Here’s what the documentation suggests:

Incoming requests to a server should create a Context, and outgoing calls to servers should accept a Context. The chain of function calls between them must propagate the Context, optionally replacing it with a derived Context created using WithCancel, WithDeadline, WithTimeout, or WithValue. When a Context is canceled, all Contexts derived from it are also canceled.

Two important rules follow from the statement above, which we’ll explore more fully in the next few sections of this post. In summary:

- If you implement a long-running computation, you should run it in a go routine and

selectfrom eitherctx.Done()or the result channel. - If you call a downstream contextual function, e.g. a database or a follow-on microservice, you should pass it the same context.

Using Contexts in Long-Running Computations

Say you have some work to do that may take a long time. What’s a good threshold?

Frontier API responses need to be returned in a second or less. That means you get approximately:

- 500ms for processing

- 250ms in either direction for network traffic

Therefore “a long time” is likely anything that takes more than 450ms, though your needs may vary.

As for database requests, as a rule of thumb, responses should take around 20-50ms. If you’re composing transactions programatically and not in SQL, this is another estimation point. Different systems will have different response times, so it’s a best practice to measure and know for sure.

In addition, the client is likely going to set some kind of timeout on the request e.g. it will wait 5 seconds before retrying or displaying a message to the user. What happens if the client timeout is exceeded while you’re processing? The client is going to stop waiting for a response, but the server will continue handling the request (most likely a wasted effort), unless we can detect the deadline exceeded. This is where the context comes in and is crtical.

Therefore, we follow Rule #1 as follows:

If you have a function hardWork, simply move it into a go routine and return the result in a channel:

func asyncHardWork() <-chan result {

done := make(chan result, 1)

go func(done chan<- result) {

done <- hardWork()

}(done)

return done

}

Then in your service handler, select either from ctx.Done() or the result channel as follows:

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return nil, ctx.Err()

case result := <-asyncHardWork():

return result, nil

}

In this code, if the client deadline is exceeded, then the error will be returned immediately and the request handler routine will stop. While the asyncHardWork routine will continue until it’s finished, any steps after hardWork won’t continue, because the request has terminated early. Alternatively, you could create a contextual hard work. For example, if hardWork is iterative, you could check if the context is done on every pass, using a default to ensure the select is non-blocking:

func hardWork(ctx context.Context) (result, error) {

for {

// Check to ensure the context isn't canceled

select {

case: <-ctx.Done():

return nil, ctx.Err()

default:

// Keep processing the for loop

}

// Computation here

}

return result

}

Using Contexts to Share Attention Span Across Microservices

This brings us to Rule #2:

If the downstream function is contextual e.g. accepts a context as the first argument, you should always pass the same context to it.

This may seem a little unnatural. For example, you may want to give a shorter deadline to a database transaction, but you don’t know how long the client context is, which may have been passed to you from upstream processing that also took a long time. The key is to rely on the client to specify their context.

We can see this especially with database transactions:

func (s *Server) MyRPC(ctx context.Context in *Request) (out *Reply, err error) {

// Begin a database transaction assuming we have a global variable, conn, that's a

// database connection pool -- pass in the same context.

var tx *sql.Tx

if tx, err = conn.BeginTx(ctx, nil); err != nil {

return nil, status.Errorf(codes.FailedPrecondition, "could not start tx: %s", err)

}

defer tx.Rollback() // Ignore rollback if tx is committed later in function.

// Do transaction work here.

}

If the context is done, then any tx calls (e.g. tx.Query() or tx.Commit()) will return a “deadline exceeded” error, allowing the transaction to stop processing and be rolled back to ensure that the database state is not left inconsistent.

Microservice Chains and Context Handling: An Example

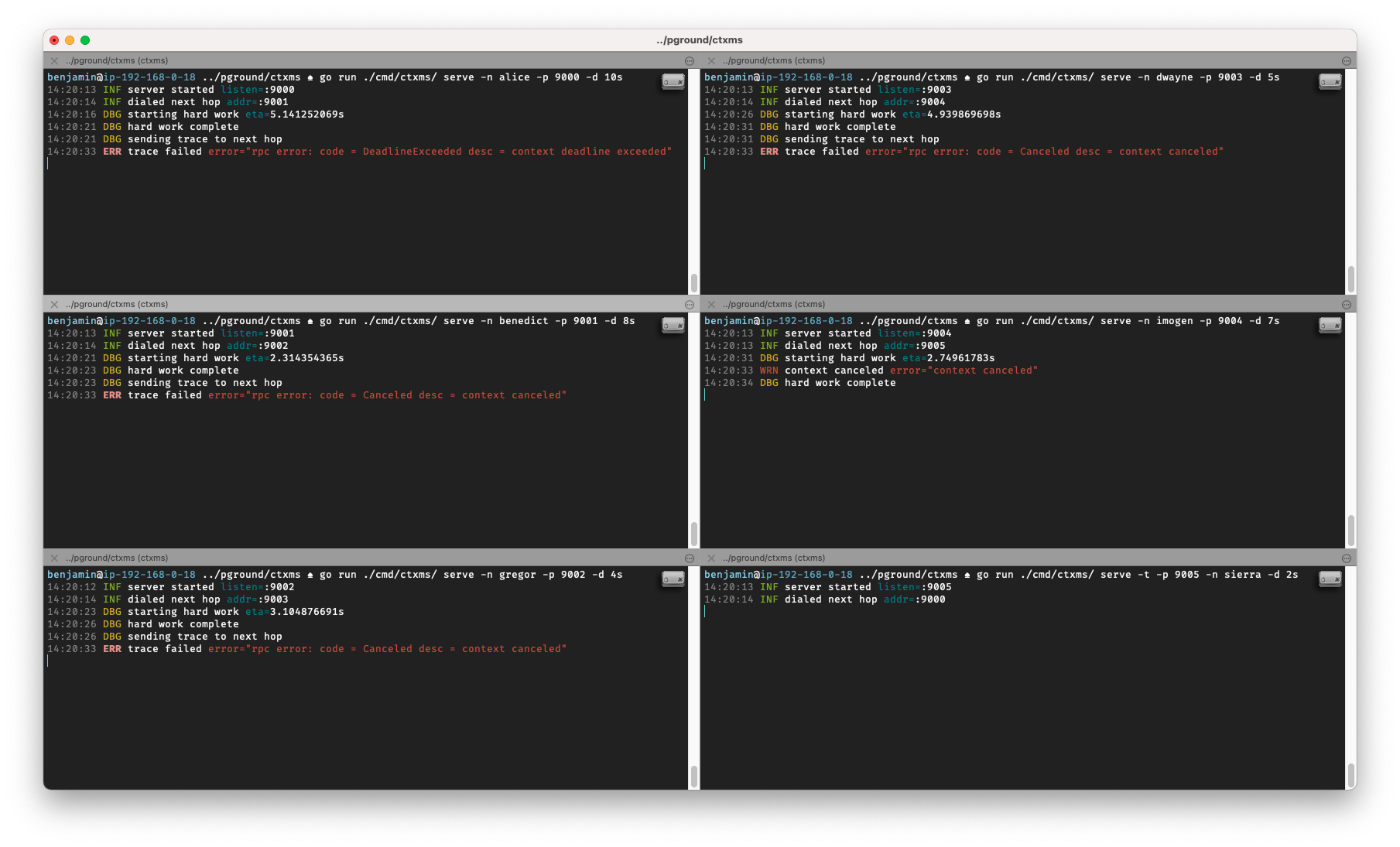

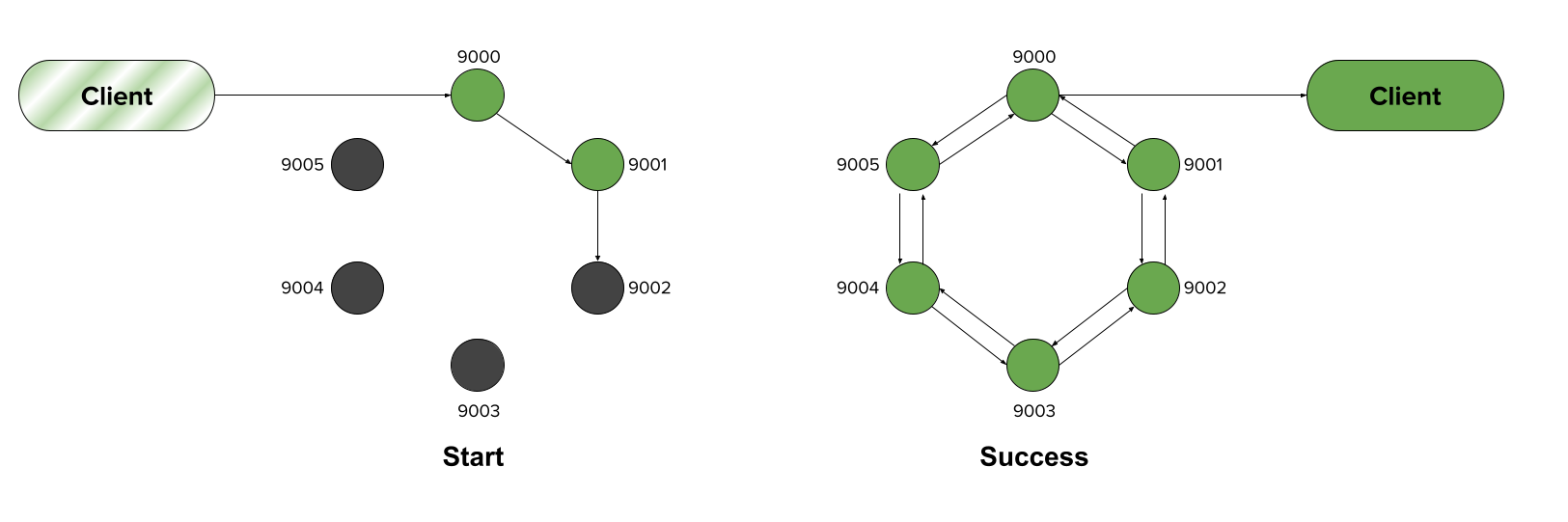

Let’s imagine that we’re building a recommender system that takes incoming data from clients, and engages a series of microservices (represented as different terminal windows below) to return a prediction.

For instance, the first service (9000) is likely our API server, which might pass data to an authentication microservice (9001) to ensure the client is allowed to access the service. The authenticator then passes the data to a data preprocessor (9002) to properly encode the values, and the result is then passed to the global modeling service (9003) for the preliminary prediction. This prediction is then passed to a personalization microservice (9004), which filters the results, before finally passing them to the metrics logging microservice (9005).

In this scenario, in order to respond to the client, each of the microservices must in turn perform some work before firing off a message to the next microservice in the loop, and triggering the next phase of work. Once the final message makes it all the way back to the API server, only then can we properly respond to the client:

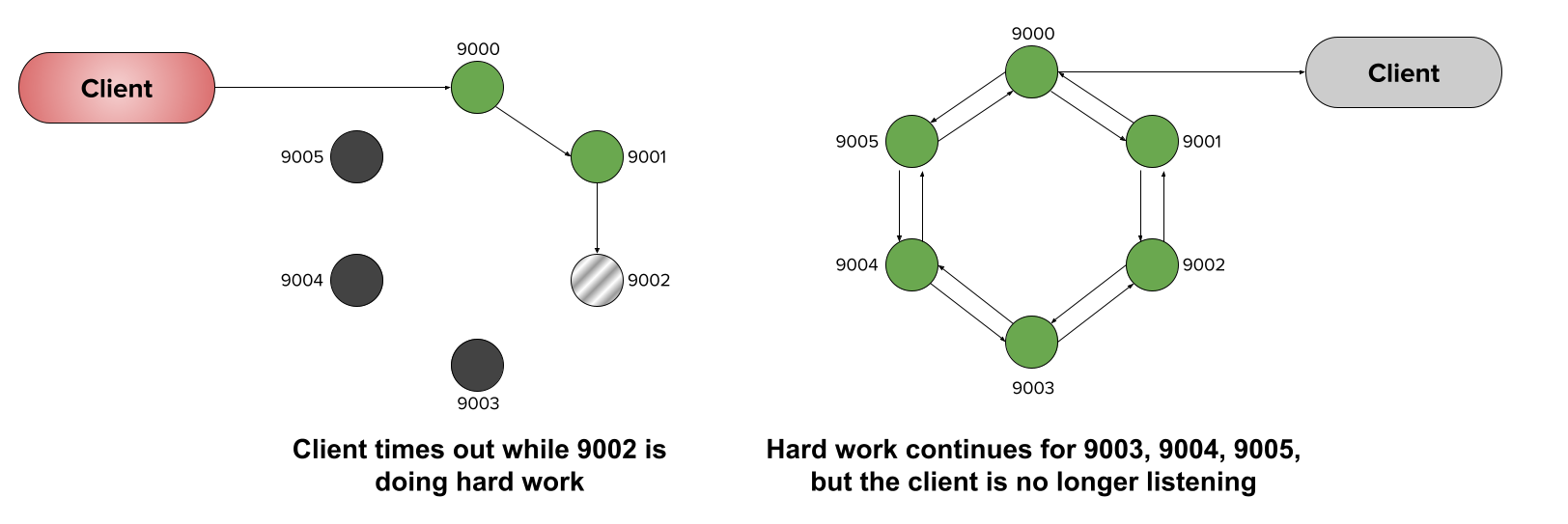

If we engineer our chain of microservices to have independent contexts, they will have no way of sharing information, such as a timeout from the client. In this case, the subsequent microservices in the chain (9003, 9004, and 9005) go on to perform hard work that is no longer needed, since the client is no longer waiting for the response:

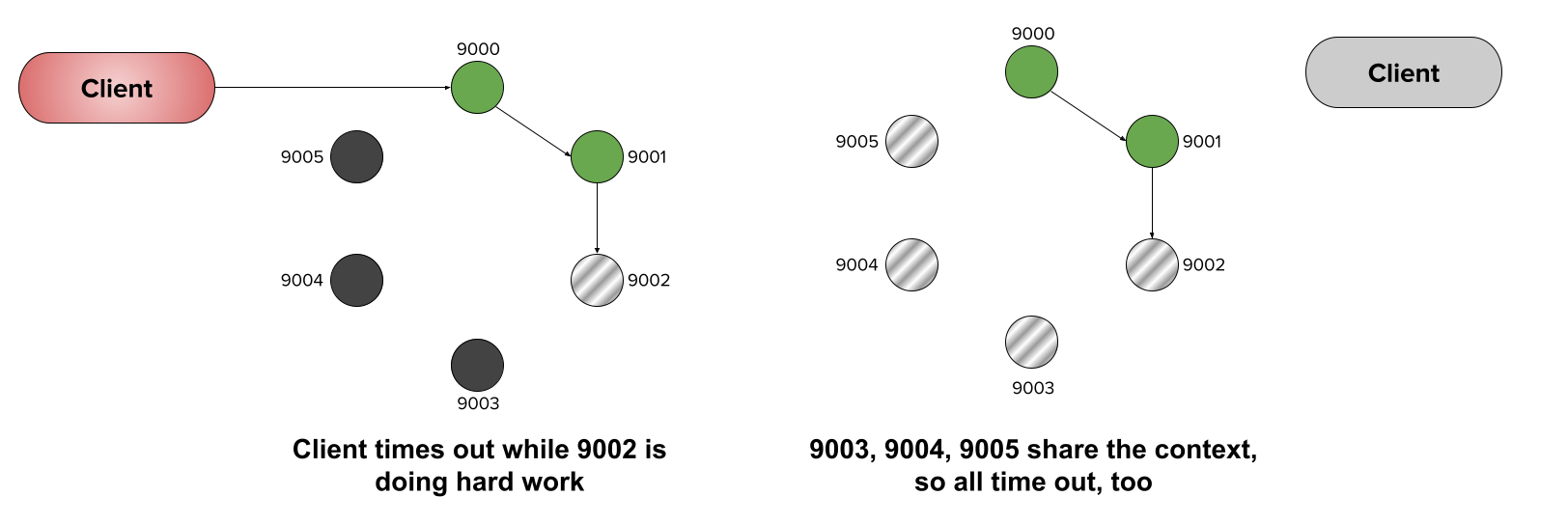

However, if our chain shares a single context, as soon as the active microservice (9002) identifies the client timeout, it breaks the chain, saving the subsequent services the trouble of performing unneeded hard work:

The Value of Shared Context

In summary, the two rules of contexts provide three distinct advantages:

(1) Contexts are the critical mechanism that allow your server implementations to be better behaved; (2) Contexts result in less processing time and memory; (3) Contexts allow your services to be more robust and effective.

Through this modest experiment, we see the value of shared context, especially as services become more complex and increasingly serve a more geographically dispersed customer base.

The code for experiment can be found at: github.com/rotationalio/ctxms.