To say we are not at our most empowered when trying to communicate in an unfamiliar language is a bit of an understatement. As if the limitations of one’s own language weren’t bad enough, trying to get along in a different language often makes you feel downright helpless. Research suggests these feelings also strongly inform consumers’ buying decisions. What does this mean for companies who want to connect with users in other countries and cultures? In this post we’ll explore some of the drawbacks of using English-only as a sales medium, check out some creative solutions, and consider what this all means for global app development.

Why Not Just English?

In David Sedaris’ (2000) “Me Talk Pretty One Day”, the author recounts his time as a new student in a French language class for adults:

The first day of class was nerve-racking because I knew I’d be expected to perform. [The teacher] proceeded to rattle off a series of administrative announcements: “If you have not meimslsxp or lgpdmurct by this time, then you should NOT be in this room. Has everyone apzkiubjxow? Everyone? Good, we shall begin.”

The administrative context is enough to transform what would otherwise be a low-stakes situation into a stressful one — it’s one thing to miss every few words of a menu or a movie in a different language, and quite another to not fully understand a legal, political, or financial choice due to unfluency.

In a survey of international consumers and firms, Donald DePalma, Benjamin Sargent, and Renato Beninatto found that language has a big impact on global consumer buying decisions:

…more than half our sample (52.4%) buys only at websites where the information is presented in their language. More than 60 percent of consumers in France and Japan told us they buy only from [websites in their own language]. (CRWB 2006)

In their 2006 report, “Can’t Read, Won’t Buy: Why Language Matters”, DePalma et al highlight one theme in particular; unless you’re already a wildly successful international brand, using English-only as a sales medium will alienate people in other countries who either don’t speak English at all, or don’t use it as a primary language.

The assumption that potential buyers ‘probably speak English’ drives inadequate localization, warring against the gut feeling that people are unlikely to buy products they cannot understand or that do not appeal to them. (CRWB 2006)

Is the problem just about language? No, it’s also about meeting consumers where they are in terms of the ways in which they are used to spending:

Even with information available in the local language, the inability to use their own credit cards or currency stymies many international buyers. (CRWB 2006)

The relative cost of the good or service is also significant, and it’s important to note that determining what cost should be — e.g taking into account the local economic circumstances — is also a crucial component of effective localization:

The more valuable an item, the more likely it is that someone will want to read about the product and buy it in their own language. (CRWB 2006)

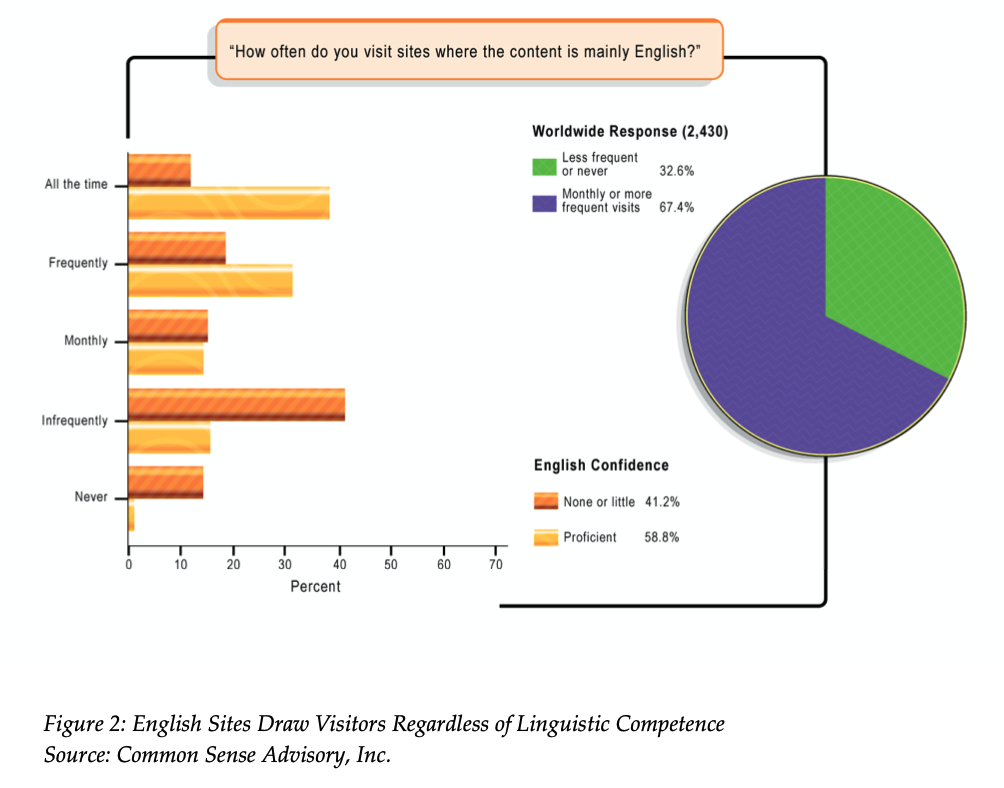

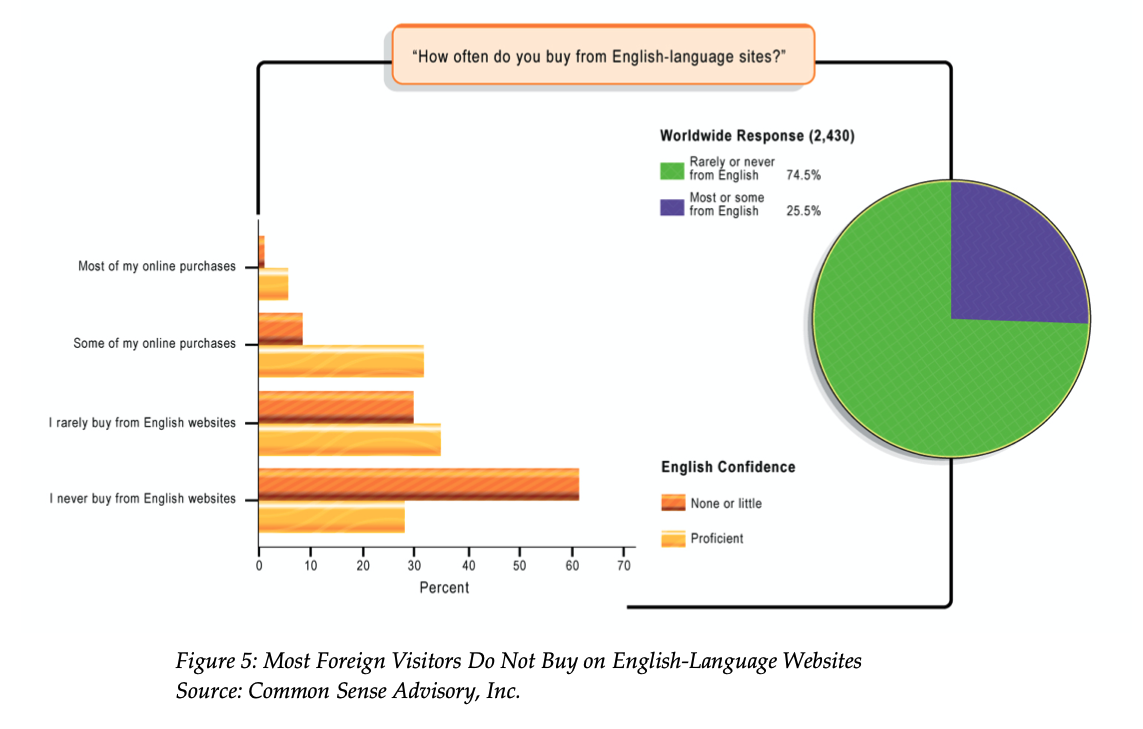

However, language is the primary blocker to successful internationalization; while 67.4% of the non-native English speakers polled said they regularly visited English-language websites, 74.5% rarely or never go on to make purchases there.

Why Not Just English, Specifically?

In “Can’t Read, Won’t Buy”, DePalma et al propose that the problem is not with English specifically, and that the same kinds of localization problems can take place anywhere:

we consider English to be a proxy for any language in which a company chooses to market to people who speak a different tongue. (CRWB 2006)

On the other hand, English is somewhat unique in that it has been the language of colonialism for so many cultures around the world. As such, English has played a not-exactly-neutral role in it’s own proliferation. In many cases, English was forced upon indigenous communities, and understandably may still serve as a symbol of aggressive assimilation and the destruction of local languages and practices. Does that history of cultural and linguistic violence come to bear on modern consumer behavior?

After all, language is just as much about identity as it is about words. As Gregory Warner, host of the NPR podcast Rough Translation, puts it:

The process of remaking yourself in another language is about a lot more than grammar or pronunciation.

Warner recently produced a story called “How to Speak Bad English”, about an English teacher, Heather Hansen, who has spent the second half of her career trying to make up for the way she taught English in the first half.

Hansen started her career giving her students what she thought they wanted — assistance in the perfection of their grammar, the eradication of non-standard pronunciations, essentially to speak just like her. Only later did she begin to see this work as a form of linguistic imperialism that hindered effective communication:

English is the most widely spoken language in the world, and the vast majority of English speakers learned the language in a classroom. Yet, in conference rooms and language courses around the world, they are often told they speak “bad English.” [When in fact] “bad English” — with its simplified vocabulary, fueled by the contributions of non-native speakers around the world — might be more universally understandable.

A striking detail discussed in the podcast is that groups of non-native speakers communicate more effectively in English when there is no native English speaker present; the introduction of a single native English speaker to a conversation begins to increase the number of conversational hiccups and misunderstandings. It’s hard not to imagine that power dynamics might have something to do with this interference. There are strong elements of psychological safety and trust at play.

Indeed, even translation from English into other languages can be a slippery slope. As we’ve discussed in a prior post, many of the language models used to power commercial Machine Translation products are trained first with English text. This means that the model’s initial and primary way of understanding the world — metaphors and idioms, sports references, even regionalized spellings — are strongly rooted in English language and Western ways of thinking. All subsequent training is necessarily constrained by these initial influences.

Creative Localization

So if you’re an app developer writing software in the US, how are you going to connect with potential customers in Asia, Africa, South America or Europe without falling into one of these linguistic traps?

Online game developer King, a division of Activision Blizzard, recently invited gamers to participate in a live presentation by the company’s Globalization team. Producer of popular games including Candy Crush and Bubble Witch, King has an enviable 240 million monthly active users across web, social and mobile platforms. Headquartered in London and Stockholm, and with studios and staff in both Europe and North America, King’s strategy for building inclusive games involves creatively adapting them to draw from cultures around the world.

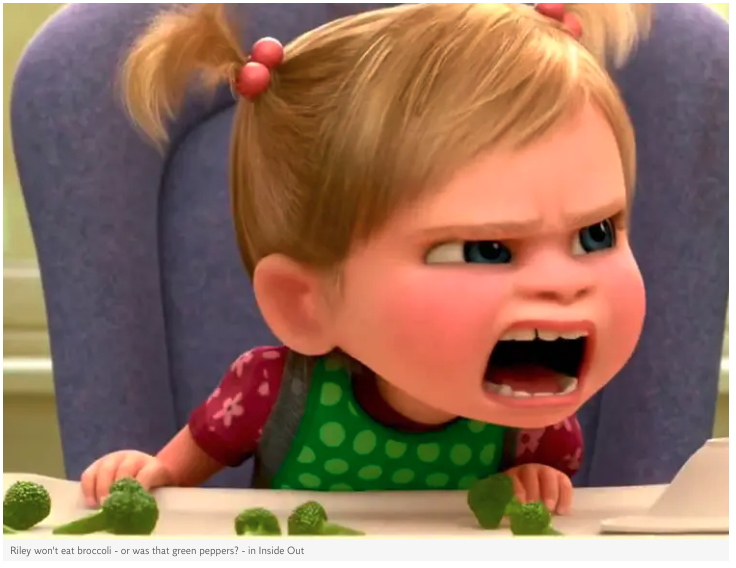

One example that came up during the discussion was from the 2015 animated movie Inside Out. As the Independent reported:

Kids in Japan love broccoli so much that Pixar had to change the cause of its child protagonist’s food hell from the tree-shaped vegetable to green peppers. In the UK and US version of the animation’s main character Riley can be seen throwing tantrums in disgust at the idea of eating broccoli for dinner. But because the vegetable doesn’t have such a poor reputation among Japanese kids it was replaced with green peppers which are generally considered disgusting.

One takeaway from the King presentation was the value of LQA — Localization Quality Assurance — particularly when performed by people who are genuine participants in the local culture. In tech, we tend to think about QA (Quality Assurance), in terms of testing out the functionality of the software, catching bugs in the user interface, detecting sequences of actions that can cause the app to crash, etc. LQA is focused on testing out the linguistic and cultural features of an app — finding word connotations that feel unnatural, identifying names that may signal prejudice, and spotting imagery that could be seen as culturally insensitive.

Miguel Sepulvida, Director of Globalization at King Games, believes that translation is only the beginning. In an interview with Inlingo, he said:

We are going to start seeing some awareness about moving away from the words. Moving away from just putting the source into the target language and just pure translation to start having more questions about how the text might be perceived in China, in Russia, or in Korea.

King is ahead of the curve — during the live presentation, an audience member asked Sepulveda whether King had noticed any relationship between investment in globalization and the company’s bottom line. The answer was a resounding “Yes!” Clearly for King, creative localization and LQA have been good for business.

The Future of Localization

What does all mean for app developers who are hoping to release software to geographically distributed audiences? It seems that there are several key challenges that such organizations will have to tackle; from the technical challenges of distributed systems to the recognition that English-only may not be a sufficient sales medium — and perhaps even more importantly, to learning how rich historic contexts and cultural experiences can inform the buying preferences of potential customers around the globe. Afterall, app developers know that the key to growth and impact is trust and engagement with end users; localization is increasingly important to those objectives. King Games proves localization is the future.

References

- David Sedaris (2000) Me Talk Pretty One Day

- Donald DePalma, Benjamin Sargent, and Renato Beninatto (2006) Can’t Read, Won’t Buy

- Gregory Warner (2021) “How to Speak Bad English”

- Heather Hansen (2018) 2 Billion Voices: How to speak bad English perfectly

- King (2021) Virtual event - A Kingdom Exclusive - Live Series with Chen and Miguel!

- Inlingo (2019) An Interview with Global Localization Manager at King, Miguel Sepulveda

- Inlingo (2021) What is Localization Testing and Why is it Important?

- Matilda Battersby (2015) Inside Out: Pixar makes crucial change for Japanese audiences by editing out broccoli