In the third and final part of our series exploring the popular consensus algorithm we’ll finally explore how Raft handles leader election, and in doing so discover how Raft is so incredibly resilient.

If you missed part 1 or part 2, check those out first!

Follow the Leader

In the last post, we broke down the AppendEntries RPC, focusing on how Raft ensures safety in log replication. When implementing Raft, be extra careful that you get AppendEntries right, because bugs can end up overwriting data or introduce a fork, where two nodes in the system diverge and produce entirely different sets of changes in their databases. Yikes!

There’s one final thing we need to cover about AppendEntries that will be very important for safety, which is leader election.

Raft is a leader-oriented consensus protocol (other single leader protocols include Paxos and Calvin). Some protocols like ePaxos and MDCC approach commits optimistically, as in, they hope for the best — assuming it’s relatively unlikely that two different clients will attempt to update the same key concurrently, and that dealing with conflict is a special case that can usually be avoided. That’s a big performance opportunity because you can let independent parts of the system make decisions at the same time, rather than having to wait to agree on every single thing first.

As leader-driven protocols, Raft and Paxos are pessimistic, assuming that conflict is sufficiently likely to require a single decision-maker to avoid them. However, it’s important to keep in mind that Raft and Paxos expect routine leader turnover — just because Alpha was the leader 5 minutes ago doesn’t mean we can assume Alpha is still the leader. Why not? Because distributed systems experience failure all time, and it’s entirely possible that Alpha has crashed in the last 5 minutes.

So how do you know when the leader is dead?

Heartbeats

We mentioned in part 2 that the leader in Raft periodically sends out “heartbeats” to let the followers know that it is still alive and well. This happens to be done using AppendEntries. If a follower receives a typical AppendEntries request from the leader it can consider that a heartbeat from the leader, but we can’t simply rely on those alone. If a leader doesn’t receive requests from clients then there would be no heartbeats!

Instead, a leader periodically (say, every n seconds or so) will send an AppendEntry request without any new log entries to all of the followers. Followers can then tell this is a heartbeat from the leader and reset their election timeout, preventing a new election and therefore a new term. Speaking of which, it’s time to move on to the final RPC in Raft.

Introducing Leader Election

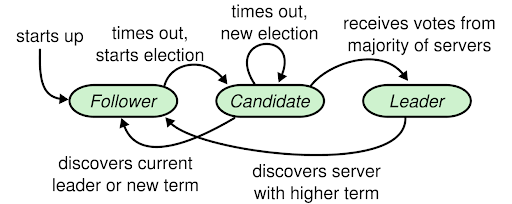

Leader election in Raft is handled by the RequestVote RPC. First off, remember at the start of this series we mentioned that there are three states that a Raft server can be in: Leader, Candidate and Follower. We haven’t talked about the candidate state yet because this is where it actually comes into play.

If a Raft server does not receive any communication from the leader (heartbeat or regular requests) for a given amount of time, it will assume the leader has died and will start a campaign to become the new leader, incrementing its term, voting for itself and sending RequestVote RPCs to the other servers in the cluster. If it receives a majority of the cluster’s votes, it declares itself leader and starts sending out heartbeats. Luckily for us, the RequestVote RPC ends up being much simpler than AppendEntries, but we should still spend some time stepping through it.

RequestVote Steps

The RequestVote function is how candidates carry out elections in remote replicas. The function expects as input a VoteRequest, which contains the candidate’s term, its unique identifier, and some details of its last log entry.

Note: Abbreviated for clarity

message VoteRequest {

int32 term = 2; // The candidate's term.

string candidateId = 3; // ID of candidate requesting a vote.

int64 lastLogIndex = 4; // The index of candidate’s last log entry

int32 lastLogTerm = 5; // The term number of candidate’s last log entry

}

In return, each voter will respond with a VoteReply, which contains their own unique identifier, their perspective of the term, and their vote.

message VoteReply {

string id = 1; // ID of the Raft node sending the vote.

int32 term = 2; // Current term number

bool voteGranted = 3; // True if the voter has voted for the candidate

}

1. Vote “no” if the candidate is behind

Just like in AppendEntries, we first need to check if the candidate has an up-to-date term. If the candidate requesting the vote has a term less than the recipient’s term, that candidate is not up-to-date with the rest of the cluster, and should be denied the vote. On the other hand if the candidate has a term greater than ours, we should ensure that we are a follower and reset our election timeout since we know there is a node in the cluster more up to date.

2. Vote “yes” if the candidate is ahead or even (but only vote once!)

Each server in a Raft cluster keeps track of who it has most recently voted for (until the next successful heartbeat). If this votedFor field is null, then it hasn’t voted for anyone in the current term and is free to vote for the candidate that sent the request.

Here’s the full logic for the RequestVote function:

func (s *RaftServer) RequestVote(ctx context.Context, in *api.VoteRequest) (out *api.VoteReply, err error) {

s.Lock()

defer s.Unlock()

out = &api.VoteReply{Id: s.id, Term: s.currentTerm, VoteGranted: false}

lastLogIndex, lastLogTerm := s.lastLogIndexAndTerm()

// Check if the incoming request has a higher term than ours, if so then there is a node in the cluster

// more up to date, so we ensure we are a follower and reset our election timeout

// Note: It's important that we return this node's current term so that the requester can check if it is

// out of date and if so, do the same (revert to follower and reset its election timeout)

if in.Term > s.currentTerm {

// Note: When implementing Raft logging is extremely helpful

fmt.Printf("RequestVote: in.Term > s.currentTerm, reverting to follower\n")

s.becomeFollower(in.Term)

}

// This (very complicated) check is to make sure the following things are true before granting the vote:

// 1. This nodes current term is the same as the requester's term

// 2. This node hasn't voted for another candidate (to prevent nodes from voting twice)

// 3. The lastLogTerm and LastLogIndex of the requester is at least up to date with this node's

if s.currentTerm == in.Term && (s.votedFor == in.CandidateId || s.votedFor == "") &&

(int(in.LastLogTerm) > lastLogTerm || (in.LastLogTerm == int32(lastLogTerm) &&

in.LastLogIndex >= int64(lastLogIndex))) {

fmt.Printf("granting vote to %v\n", in.CandidateId)

out.VoteGranted = true

s.votedFor = in.CandidateId

s.lastHeartbeat = time.Now()

}

return out, nil

}

So, to sum it all up, the first job of the RequestVote RPC is to determine if the recipient itself is a candidate for election; the recipient will check to see if it is behind the requesting candidate’s term, and if so, will become a follower. If the recipient is actually ahead of the candidate, it will notify the candidate that it is not eligible for election by passing it’s current term back to the candidate. This helps enforce Raft’s guarantee that there is only one leader at a time, and is important to determine early on to prevent the recipient from concurrently mounting its own campaign or for an ineligible candidate to repeatedly seek election (both of which can cause election thrashing).

Next, the recipient must determine whether it can vote for the candidate. The requirements for that decision are: (1) their terms must match (2) the recipient must not have already voted for another candidate (3) the most recent entry in the requesting candidate’s log must have either the same term or a later term than the recipient’s most recent log entry, and (4) the requesting candidate’s log must not be shorter than the recipient’s. If all these checks pass, the recipient will grant the candidate it’s vote.

Wrapping Up

And that’s a high level summary of the Raft algorithm! If you want to take a crack at implementing the algorithm I would encourage you to read the original whitepaper by Diego Ongaro and John Ousterhout. It will give you a deeper dive into the algorithm and provide some explanations for more advanced topics in Raft like configuration changes and snapshots.

Writing your own implementation of Raft is definitely a difficult task, but if you’re at all interested in distributed systems it’s a fantastic way to get started down the path of learning about the field. For further reference you can check out my experimental implementation of Raft. If you missed the first two parts of my Raft series you can find part one here and part two here.