With all the blockchain breaches and social media escapades, there’s been an awful lot of buzz about distributed systems lately. But how many of us really understand how they work? Let’s dive in together…

As the focus of modern applications becomes global, distributed systems are becoming a more and more routine part of software engineering. The question comes down to this: “How can we maintain availability with our applications and prevent data loss when servers inevitably crash?”

This brings us to the topic of consensus algorithms, and in particular, the focus of this series of blog posts: the Raft consensus algorithm.

Consensus allows for the data contained in globally distributed servers to be replicated across multiple machines to prevent losses of either availability or data. Consensus algorithms are a class of provably safe, algorithmic mechanisms for enabling multiple servers to agree on a single value or a series of values (i.e. a log). They can be used for any generic data-generating process we might want to keep consistent, whether that’s a file system, an event broker or any other kind of storage mechanism. Raft is perhaps the most popular of the consensus algorithms, and a perfect way to start learning about consensus!

Introducing Raft

First published in 1989, Leslie Lamport’s Paxos algorithm was the first widely known mechanism for enabling state machine replication in a distributed context. This means that it can be used to enable a group of servers to remain in a consistent state by collectively producing a single, totally ordered, log of operations on which they all agree.

Strong consistency is a critical feature for many applications (think: banking, voting, etc.), because it engenders a high degree of trust across all users that the data will be the same no matter where they are geographically. By contrast, high availability systems frequently allow some to see stale data in return for quicker application response times.

Paxos has a reputation for being difficult to understand and implement. Raft is a similar protocol (technically an optimization/reframing of Paxos) published in 2014 by Diego Ongaro and John Ousterhout, and is designed to alleviate these difficulties. Because of this, it makes for a good place to start learning about the wide world of consensus algorithms.

The Basics

A Raft peer set is a group of servers that cooperate to keep their logs consistent with each other; a subset of these peers play an active role in the process (the quorum).

A Shareable Log

The core data structure in consensus is the Log, an ordered sequence of operations that each peer applies to update its state. Each member of the peer set maintains a local copy of the log, but in a distributed context, the log generally refers to a peer set’s collective understanding of the sequence of events – including which events have occurred and the order in which they occurred.

Follow the Leader

Each server in a Raft quorum is at any time in one of three states. These roles may seem simple enough, but much of the complexity in implementing Raft is in writing code to effectively detect which of these states a given server is in (and the source of most bugs).

- Leader

- Follower

- Candidate

Raft is a leader-driven algorithm. In a Raft quorum there can only be one leader at a given time and that leader is responsible for accepting requests and determining when the log should be updated. Raft is based on the principle that requests flow one way. When a new client request comes in, it should be routed to the Leader, which will take action and then pass on the new information to the rest of the Followers. The Leader is also responsible for sending periodic heartbeats to its Followers to let them know it is still active.

Followers are in charge of two things, responding to the leader’s requests (such as to append new entries to their log) and, in the case that a Follower hasn’t heard from the Leader in a long enough time, starting an election to assume the Leader role.

A Candidate is a Follower who, finding that it has not received a heartbeat from the Leader for a certain amount of time, is attempting to become the new Leader.

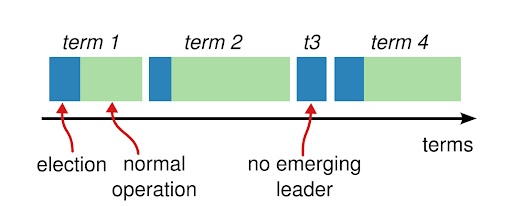

In Terms of Time

Time in Raft is divided into what it calls Terms (or Epochs). Terms in Raft are equivalent to each leader’s reign (as in a president’s term in office); if an election is triggered and a new leader is decided on, a new term begins. Each peer in a Raft quorum is responsible for keeping track of the current term. Terms are used in Raft to allow servers to correctly order entries in the log and ensure that there is only one leader at a given time.

It should be noted that leaders also keep track of which log entries are considered committed. An entry is committed if the leader has received confirmation that it has been replicated to a majority of servers. Once an entry is committed Raft guarantees that that entry is durable and will eventually be replicated to all other servers.

Next Time…

That’s it for the basics of Raft. In the next part of our series we’ll start peeking into the inner workings of Raft’s log replication by learning about the first of its two remote procedure calls. If you want a preview, check out this experimental implementation of the Raft algorithm done as a continuous learning exercise.

Resources

Lamport (1998) The Part-Time Parliament

Ongaro and Ousterhout (2014) In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm