The Go programming language provides powerful tools for managing concurrency, but robust asynchronous code requires us as developers to design around uncertain tasks and manifold queues. Step through an async codebase with us in this post!

What’s an Async Task?

If you’re a developer like me, you avoid introducing concurrency when it’s not necessary.

Concurrency is a double-edged sword that enables things like vector processing on graphics cards and eventing systems, but is notoriously difficult to understand, debug, and maintain. Unfortunately, if you’re building services for users, being able to service simultaneous requests is unavoidable. Hopefully you’re using a database equipped to handle concurrent updates and resolve consistency issues. (If you aren’t sure, it may be time to get a bit more familiar with your data layer.)

While building Ensign, we needed a way to not just service user requests, but schedule tasks to happen “sometime in the near future”. For example, if a user logs into the system, we want to update their last_login timestamp in a database. This doesn’t need to happen immediately since it’s not a critical step for giving a user access to the system, but it should happen eventually. In distributed systems terminology, that’s eventual consistency. (Looking for an entertaining introduction to distributed systems?.)

So let’s build an asynchronous task manager in Go!

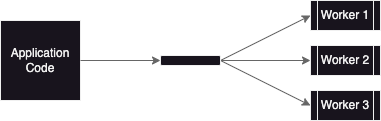

The Minimal Task Manager

The task manager should provide an interface for the programmer to execute code without blocking the current thread. We should also consider the following points if we have to run this in production:

- The amount of concurrency should be limited to avoid overloading the server.

- The number of tasks should be limited to avoid running up the memory usage.

Fortunately, Go has some great concurrency builtins, which are probably why you’re using Go in the first place. We can create a buffered channel, which acts as a bounded queue — writing to the queue only blocks if the queue is full, and reading from the queue only blocks if the queue is empty. This is similar to Python’s asyncio.Queue but allows us to send “tasks” between go routines.

To limit the amount of concurrency, we can employ a worker pool pattern and only run the configured number of worker routines. The job of a worker is to pull tasks off the queue and execute them. The beauty of Go channels is that we don’t have to worry about synchronizing the workers with a global lock.

package tasks

type Task interface {

Do(context.Context)

}

// TaskFunc is an adapter to allow ordinary functions to be used as tasks.

type TaskFunc func(context.Context)

func (t TaskFunc) Do(ctx context.Context) {

t(ctx)

}

// TaskManagers execute Tasks using a fixed number of workers that operate in their own

// go routines.

type TaskManager struct {

wg *sync.WaitGroup

queue chan<- *TaskHandler

}

// TaskHandler wraps a Task with a context.

type TaskHandler struct {

task Task

ctx context.Context

}

// New returns TaskManager, running the specified number of workers in their own Go

// routines and creating a queue of the specified size. The task manager is now ready

// to perform routine tasks!

func New(workers, queueSize int) *TaskManager {

wg := &sync.WaitGroup{}

queue := make(chan *TaskHandler, queueSize)

for i := 0; i < workers; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go TaskWorker(wg, queue)

}

return &TaskManager{wg, queue}

}

// Stop the task manager waiting for all workers to stop their tasks before returning.

func (tm *TaskManager) Stop() {

close(tm.queue)

tm.wg.Wait()

}

// Queue a task with a background context. Blocks if the queue is full.

func (tm *TaskManager) Queue(ctx context.Context, task Task) {

tm.queue <- &TaskHandler{task, ctx}

}

func TaskWorker(wg *sync.WaitGroup, queue <-chan *TaskHandler) {

defer wg.Done()

for handler := range queue {

handler.task.Do(handler.ctx)

}

}

Then all we have to do from the application code is define and execute the task!

tasks := tasks.New(8, 64)

task := func(ctx context.Context) {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 1*time.Minute)

defer cancel()

if err := user.UpdateLastLogin(ctx); err != nil {

// Log the error so we know that this failed

}

}

tasks.Queue(tasks.TaskFunc(task))

Note: Passing in a context helps prevent tasks from running forever, assuming that the underlying code actually respects the context.

If at first you don’t succeed…

The above is functional, but sometimes we need a way to retry failing tasks. For example, sending an email is prone to intermittent failure, since it relies on external systems. We might want to retry it a few times to ensure that users actually receive the email. A good retry mechanism also supports backoffs. If we retry the task immediately there’s a good chance it will fail again, but if we wait for a bit, there’s a better chance that transient errors like network issues will be resolved (this is why you will see CrashLoopBackoff and ImagePullBackoff states for pods in k8s).

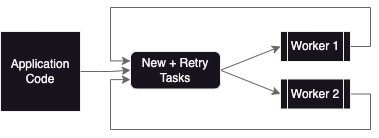

One solution is to have the workers be responsible for putting tasks back onto the queue if they need to be retried. Maybe we want something like the below revised architecture diagram?

Getting warmer, but the fact that everything is writing back to the same queue is a red flag. Consider the case where the queue is already full with tasks from the application. Remember that buffered channels block on writes if the channel is full. If a worker needs to retry a task, it will be stuck trying to write to the queue. Even worse, if all workers are blocked then the application won’t be able to queue new tasks and the system goes into full deadlock!

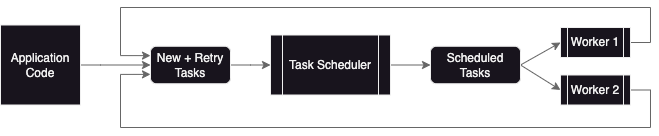

The solution is to introduce more control over the queue. We can create another go routine, a tick-based TaskScheduler, which is responsible for scheduling both new and retryable tasks, and will work hard to avoid the deadlock situation. The improved architecture looks something like this:

Note that there are now two queues, which help us distinguish between brand new tasks and scheduled tasks. This allows us to further isolate the responsibilities of the task scheduler and the workers. Although there is still some recursive madness, the scheduler has the ability to ensure that both queues remain unblocked.

Task Scheduler

The key to preventing deadlocks is to “hold” pending tasks in the scheduler. We don’t want to put them on the queue if they aren’t ready, since this creates the situation discussed previously. The pending tasks are actually another form of queue, but in this implementation it’s unbounded to make sure the workers can make progress. Note: This means we have to be really careful to avoid leaking memory.

func TaskScheduler(wg *sync.WaitGroup, queue <-chan *TaskHandler, tasks chan<- *TaskHandler, stop <-chan struct{}, interval time.Duration) {

defer wg.Done()

// Hold tasks awaiting retry and queue them every tick if ready

pending := make([]*TaskHandler, 0, 64)

ticker := time.NewTicker(interval)

defer ticker.Stop()

for {

select {

case task := <-queue:

// Check if the task is a retry task that needs to be held

if !task.retryAt.IsZero() && time.Now().Before(task.retryAt) {

pending = append(pending, task)

continue

}

// Otherwise send the task to the worker queue immediately

// Do not block the send; if no workers are available, append the task to

// the pending data structure. This will reduce the backpressure on the

// queue but also prevent deadlocks where there are more retries than

// workers available and no one can make progress.

select {

case tasks <- task:

continue

default:

pending = append(pending, task)

}

case now := <-ticker.C:

// Do not modify pending if it contains no tasks.

if len(pending) == 0 {

continue

}

// Check all of the pending tasks to see if any are ready to be queued

for i, task := range pending {

if task.retryAt.IsZero() || task.retryAt.Before(now) {

// The task is ready to retry; queue it up and delete it from pending

// Note: this is a non-blocking write to tasks in case there are no

// workers available to handle the current task.

select {

case tasks <- task:

pending[i] = nil

default:

continue

}

}

}

// Prevent memory leaks by shifting tasks to deleted spots without allocation

i := 0

for _, task := range pending {

if task != nil {

pending[i] = task

i++

}

}

// Compute the new capacity, shrinking it if necessary to prevent leaks.

newcap := cap(pending)

if i+64 < newcap {

newcap = i + 64

}

pending = pending[:i:newcap]

case <-stop:

// Flush remaining tasks to the workers

for _, task := range pending {

tasks <- task

}

close(tasks)

return

}

}

}

Workers

Workers need only know how to execute a task and if a retry needs to be queued. We can put some state in the TaskHandler to ensure that we keep track of the number of attempts, etc. If a retry needs to be done, the worker just sends it back to the original queue for the scheduler to process.

type TaskHandler struct {

parent *TaskManager

task Task

opts *options

ctx context.Context

err *Error

attempts int

retryAt time.Time

scheduled time.Time

}

func TaskWorker(wg *sync.WaitGroup, tasks <-chan *TaskHandler) {

defer wg.Done()

for handler := range tasks {

handler.Exec()

}

}

// Execute the wrapped task with the context. If the task fails, schedule the task to

// be retried using the backoff specified in the options.

func (h *TaskHandler) Exec() {

// Attempt to execute the task

var err error

if err = h.task.Do(h.ctx); err == nil {

// Success!

return

}

// Deal with the error

h.attempts++

h.err.Append(err)

// Check if we have retries left

if h.attempts <= h.opts.retries {

// Schedule the retry be added back to the queue

h.retryAt = time.Now().Add(h.opts.backoff.NextBackOff())

h.parent.queueTask(h)

return

}

// At this point we've exhausted all possible retries, so log the error.

h.err.Since(h.scheduled)

h.err.Log(log.Logger)

h.err.Capture(sentry.GetHubFromContext(h.ctx))

}

func (tm *TaskManager) queueTask(handler *TaskHandler) error {

// The read-lock allows us to check tm.stopped concurrently. If Stop() has been

// called it holds a write lock that prevents this lock from being acquired until

// the scheduler has closed the queue.

tm.RLock()

defer tm.RUnlock()

if tm.stopped {

// Dropping the task because the task manager is not running

log.Warn().Err(ErrTaskManagerStopped).Msg("cannot queue async task when task manager is stopped")

return ErrTaskManagerStopped

}

// Queue the handler

tm.queue <- handler

return nil

}

Final Thoughts

There’s just no doubt about it — it’s hard to reason about asynchronous processing! No matter how senior you get, concurrency is hard.

But being able to name your problem is most of the battle, and hopefully the example in this post helps illustrate some of the hazards to watch out for!

Want more? Check out the Ensign repo on GitHub!

If you’re looking to add more concurrency to your architecture, check out Ensign, a platform and community for developers building asynchronous apps.