The most exciting applications coming out these days are the ones that aim big — aspiring to reach a global audience of users across regions, languages, timezones, and data centers. Not only are they in the exhilarating position of owning planet-scale markets, they’re poised to take on some of the most interesting data systems problems we’ve ever seen!

Of course, it’s easy to get lost in the maze of algorithms, protocols, and terminology related to distributed systems. It’s a complex topic and there are a lot of good approaches, most of which leverage strategic optimizations that further confuse the underlying principles.

Most of the talented engineers and technical executives I know get lost in the details of two fundamental concepts: coordination and consistency. In this post, we’ll take a look at distributed systems through a metaphor — a robot stuck in a maze — to illustrate why coordination is necessary (and difficult!), and what exactly creates consistency issues. A bit fanciful? Sure, but hard to forget!

Coordination

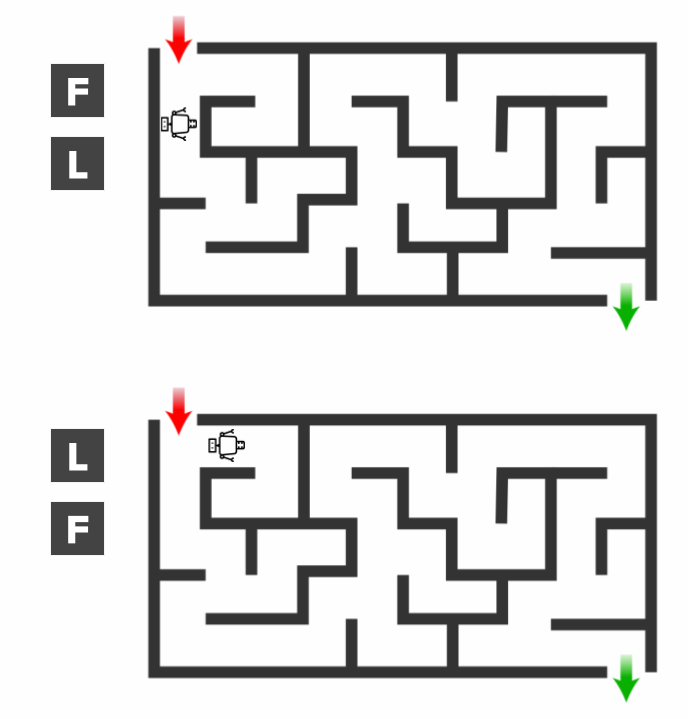

Imagine there are two robots trying to find their way through the same exact maze in two different buildings. Successfully completing the task requires both robots to leave the maze as quickly as possible and there is only one path that leads to the exit. The robots can communicate with each other and with human controllers that give commands to the robot remotely.

Let’s make the commands purposefully simple - the human controllers can tell their robots to turn left or right, move forward or backward, or to take and send a picture from the forward facing camera. Robots can only execute one command at a time and by default, they execute the commands in the order they receive them.

Consistency

The first coordination scenario is, well, no coordination: each robot receives and obeys commands from its human controllers, but does not communicate the commands to each other. In this case, it’s up to the human teams to both understand how many robots there are and what position each robot is in, directing their commands to each robot appropriately. In the best case, it will likely take twice as long for the robots to execute the maze - clearly, coordinating the actions of the robots is vital!

If the robots are strictly coordinated then when they receive a command from their human team they will pass the command to the other robot, then execute the command; if it receives a command from the other robot it will simply execute the command. Coordination in this scenario quickly gets out of hand: if two teams give commands to different robots simultaneously: “turn left” and “move forward”, then the first robot will turn left then move forward, while the second robot will move forward then turn left. They are now in two different positions and the more commands they get, the worse it is. It’s unlikely in this scenario that either robot will be able to leave the maze.

When the two robots end up in two different positions like this, an inconsistency has occurred. From the human controller point of view, they expected both robots to both move forward or turn left, and now when they ask for pictures from each robot, they get two different results! One way to think about coordination and consistency is the desirable property that both robots receive the commands in the same exact order so that they never end up in two different positions.

Stale Reads and Non-Conflicting Commands

We can try to fix the situation by only allowing one robot to receive commands from the human teams. This will ensure that the two robots do not end up in two different positions because the order the first robot receives commands will be the same order that the second robot receives them. However, this causes a lot of load on the first robot, slowing it down as it processes all the commands coming in. We could relax our coordination requirement and allow the “take picture” command to be executed by both robots. This scenario is often referred to as primary/backup copy in distributed systems.

Taking a picture is an interesting command because no matter what order the commands are received in, the robots will not end up in two different positions. The worst case scenario is that a robot takes a picture before it immediately moves, meaning that the human controller is looking at an old picture; e.g. the picture is stale. Another type of inconsistency is if both robots are asked for pictures but they return two different positions because they’re in different places in their command sequence; the inconsistency is from the human perspective who may believe the robots are in different positions even though the reality is that at least one image is stale.

Failures and Partitions

Robots are finicky things - what happens if the primary robot gets stuck or stops responding to commands? The robot has a self-repair feature and it will reboot if this happens, however for the duration that the lead robot is rebooting, the human controllers will be able to do nothing except take pictures from the back up robot! Time is ticking!

It is possible for the other robot to detect when the lead robot has failed — for example if it hasn’t received a message after a certain time limit. At this point, the other robot can start accepting commands, and when the first robot reboots the live robot can send a list of commands to get the other robot to the same position its in.

The Quorum

Unfortunately, the back up robot won’t be able to tell if the other robot has failed and is rebooting or if it has simple lost the ability to communicate with the other robot. If both robots are operating but can’t communicate with each other one of two things will happen: either the robots will both take commands and we’re back to the inconsistency problem, or neither robot will take action until it hears from the other, and we lose a bunch of time.

In order to make progress in the event that a single robot has failed or can’t communicate with the other robot, we need a third robot in a third maze, in a third building. Now we can engage in quorum based decision making: as long as at least two robots can communicate with each other, there is a way for them to accept commands and make progress even if one robot can’t communicate to the other robots or has started rebooting. If we want to protect from 2 possible robot failures of any type; we’ll need 5 robots in 5 buildings. A description of how this works is for another blog post; but hopefully it will suffice to say that in a 3 group system, as long as two robots are able to communicate, any combination of single failures will result in all robots applying the same command.

Conclusion

You’re probably not in the business of coordinating a fleet of robotic maze navigators. Maybe your application enables crypto payment processing. Perhaps you’re a popular game developer with an in-game currency exchange. Maybe you’re the hot new privacy-first messaging app. Nevertheless, as your user base expands across the globe, sooner or later you’ll start to feel the pains of robots in the maze.

Regardless what you’re building, the robot maze metaphor highlights the importance of coordination in a distributed system, and how different consistency issues may be observed by users of our systems. For example, what is a transaction if not just a bunch of commands bundled together and applied as a sequence? How about eventual consistency? Maybe the robots do independent exploring and have a way to select the best location to all return to after some criteria has been reached.

I hope this post creates a mental hook to understand more complex distributed systems topics — not because everyone needs to be an expert, but so that you can build out your application the way that makes sense for your business.